Ký |

Bài viết, theo GNV, tuyệt nhất về Romain Gary, trên TV đã từng giới thiệu, là Romain Gary: A Foreign Body in French Literature, RG, một cơ thể lạ trong văn chương Tây, thực sự rút gọn cuốn sách của chính tác giả, Nancy Huston, Mộ của Romain Gary, Tombeau de Romain Gary, 1995, qua đó tác giả coi Gary muốn làm một Chúa Giáng Sinh lần thứ nhì. Và

điều mà tôi toan tính làm, là, sẽ thuyết phục bạn, về một sự kiện, bề

ngoài xem

ra có vẻ quái dị khó tin, ông Romain Gary này cứ nhẩn nha nghĩ về mình,

và tạo

vóc dáng cho mình, y như là đây là Lần Tới Thứ Nhì: Romain Gary là một

tự xức dầu

thánh, tự phong chức, tự tái sinh, và, sau hết, một Chúa Cứu Thế Tự

Đóng Đinh

Chính Mình .....

The strange case of

Benjamin Black. Note: Bài viết này, có cái tít ở trang bià là "Những Lạc thú của bút hiệu", The Plesasures of pen names. Viết về trường hợp nhà văn John Banville, còn viết song song/cùng lúc với cái tên Benjamin Black. TV cũng đã

từng viết về đề tài, nhân tình cờ biết được cái nick của Mai Thảo

là Nhị, qua bài tưởng niệm

ông của TTT, và đưa ra

giả dụ, liệu Nhị, ở đây, là Nhị

Hà? Cùng lúc, trên TLS có bài điểm cuốn tiểu sử của Romain Gary. Ông này còn nổi danh với cái nick Ajar, và với mỗi cái nick, là một Goncourt! TV sẽ post

toàn bài viết, không chỉ 1 đoạn,

như The New Yorker chào hàng, vì thật

thú vị, và nhân đó, lèm bèm về GNV, cũng có hơn một cái nick, trong đó,

có

Jennifer Tran, nổi danh hơn cả GNV! Go on, run

away, but you'd be far safer if you stayed at home. Trong Tựa đề cho những bài thơ,

Foreword to the Poems, John Fowles cho rằng cơn

khủng hoảng

của tiểu thuyết hiện đại, là do bản chất của nó, vốn bà con với sự dối

trá. Đây

là một trò chơi, một thủ thuật; nhà văn chơi trò hú tim với người đọc.

Chấp nhận

bịa đặt, chấp nhận những con người chẳng hề hiện hữu, những sự kiện

chẳng hề xẩy

ra, những tiểu thuyết gia muốn, hoặc (một chuyện) có vẻ thực, hoặc (sau

cùng)

sáng tỏ. Thi ca, là con đường ngược lại, hình thức bề ngoài của nó có

thể chỉ

là trò thủ thuật, rất ư không thực, nhưng nội dung lại cho chúng ta

biết nhiều,

về người viết, hơn là đối với nghệ thuật giả tưởng (tiểu thuyết). Một

bài thơ

đang nói: bạn là ai, bạn đang cảm nhận điều gì; tiểu thuyết đang nói:

những

nhân vật bịa đặt có thể là những ai, họ có thể cảm nhận điều gì. Sự

khác biệt,

nói rõ hơn, là như thế này: thật khó mà đưa cái tôi thực vào trong tiểu

thuyết,

thật khó mà lấy nó ra khỏi một bài thơ. Go on, run away... Cho dù chạy

đi đâu,

dù cựa quậy cỡ nào, ở nhà vẫn an toàn hơn. Khi trở về với

thơ, vào cuối đời, Mai Thảo đã ở nhà. Cái lạnh, trong thơ ông, là cái

ấm, của

quê hương. Của Nhị. BIOGRAPHY Stories of a

self-made man IAN PINDAR David Bellos ROMAIN GARY A tall story 528pp.

Harvill Seeker. £30. 978 1 84343

1701 "Fraud,

imposture and charlatanism play an important role in your work",

observes

the journalist Francois Bondy, interviewing the novelist Romain Gary in

La Nuit sera calme (1974). The delicious

irony of this statement is that Gary is impersonating Bondy, who had

nothing to

do with the book. La Nuit sera calme

is one of several faux memoirs Gary produced. In it he claims his

mother was

the driving force in his life - a mother figure, David Bellos observes,

that he

mostly invented. Why did

Romain Gary invent so much about himself? Especially when, as Bellos

ably

shows, his extraordinary and in many ways enviable life was so

eventful? Gary's

mastery of the "fabricated anecdote", his "liberal use of

half-truths, subterfuges and outright lies", present enormous

challenges

to any biographer. "He hid his identity again and again," says

Bellos, "blut gave a great deal of himself away through the recurrent

motifs in his work." Born in

Russia in 1914, Roman Kacew recreated himself in France as Romain Gary

(possibly

in homage to Gary Cooper). When France fell, he served in the Free

French

squadron and wrote his first novel in a few months in 1943 while on

active

service. But Éducation européenne (A

European Education) is not remotely

about the air war he was fighting at the time. It is about Polish

partisans

resisting the Germans and, says Bellos, "Gary seems to have invented

every

bit of it". After the war Gary joined the Diplomatic Corps, living it

up

as the French consul general in Los Angeles until 1960, when he married

the

beautiful actress Jean Seberg. Always a ladies' man, he was also a

bestselling

novelist and won the Prix Goncourt with Les

Racines du ciel (1956). However you look at it, it was a wildly

adventurous

life: "Litwak, immigrant, airman, diplomat, Don Juan, novelist and

globe-trotting celebrity spouse". Gary was an

unashamedly popular novelist, but Bellos argues that his fiction was

often more

innovative than the work of the French avant-garde. Aside from a few

unnecessary

jibes at Samuel Beckett and the nouveaux

romanciers, Bellos makes a good case. "In strange and unexpected

ways," he says, "rereading Gary's intentionally middlebrow novels,

with their rattling yarns and page-turning style, has made it clearer

to me

what literature can do. Comedy, kitsch, sentimentality and high ideals

don't

have to be treated as crimes. They can also be the vehicles and the

freight of

sophisticated verbal art." Bellos

appears to lose sympathy with Gary as the biography progresses,

however.

"Gary was not an admirable person in all respects", he declares near

the end, "and in some he was monstrous, even repulsive." Bellos

reveals that Gary visited prostitutes every day and had what Bellos

calls

"near-pedophiliac proclivities". Only his diplomatic immunity while

consul general saved him from being arrested for statutory rape.

Another biographer

might have made devastating use of this, but Bellos is uncensorious and

traces

Gary's "taste for underage sex" back to the novelist’s earliest sexual

experience - deduced from a repeated scenario in his fiction - around

the age

of fourteen with a girl about the same age. Gary's "sexual gluttony"

is given meaning as a lifelong search for this original event. Gary wrote

under many names, but his most famous pseudonym is undoubtedly "Emile

Ajar", who authored three novels, one of which, La Vie

devant soi (1975; Life

Before Us), was a bestseller and would have won the Goncourt had

Ajar not

withdrawn it. Bellos's enthusiasm is rekindled with the invention of

Ajar, and

he clearly relishes the "linguistic riot" of "Ajarspeak":

"the irregular, enriched, unstable, deceptive and bastardised language

to

which Gary had always aspired". This ludic dimension (one chapter is

entitled "Games with Names") appeals to Bellos, who is, after all,

Georges Perec's biographer. Creating

Ajar "was a new birth", Gary said in his posthumously published

testament Vie et mort d'Emile Ajar (1981).

"I had the perfect

illusion of a new creation of myself, by myself." But the "Ajar

scam" soon became a nightmare for Gary, who dreaded being exposed as a

fraudster (yet he complicated matters by asking his cousin Paul

Pavlowitch to

pose as Ajar for the French media). Romain Gary shot himself in 1980,

his

suicide note observing: "I have at last said all that I have to say". As well as

being an impressive work of scholarship (Gary wrote in French and

English and

indulged in "obsessive bilingual self revisions" that make his

bibliography "devilishly complicated"), this is a profound book in

its examination of what it means to invent oneself. Like Jay Gatsby,

Romain

Gary sprang from his Platonic conception of himself. As David Bellos

tells it,

he "wanted to become a character in a novel of his own invention". In

fact, "The novelist is an invention of the text". Romain Gary, it

turns out, was just another character in a story. Bài viết, theo GNV, tuyệt nhất về Romain Gary, trên TV đã từng giới thiệu, là Romain Gary: A Foreign Body in French Literature, RG, một cơ thể lạ trong văn chương Tây, rút gọn cuốn sách của chính tác giả, Nancy Huston, Mộ của Romain Gary, Tombeau de Romain Gary, 1995, qua đó tác giả coi Gary muốn làm một Chúa Giáng Sinh lần thứ nhì. Và

điều mà tôi toan tính làm, là, sẽ thuyết phục bạn, về một sự kiện, bề

ngoài xem

ra có vẻ quái dị khó tin, ông Romain Gary này cứ nhẩn nha nghĩ về mình,

và tạo

vóc dáng cho mình, y như là đây là Lần Tới Thứ Nhì: Romain Gary là một

tự xức dầu

thánh, tự phong chức, tự tái sinh, và, sau hết, một Chúa Cứu Thế Tự

Đóng Đinh

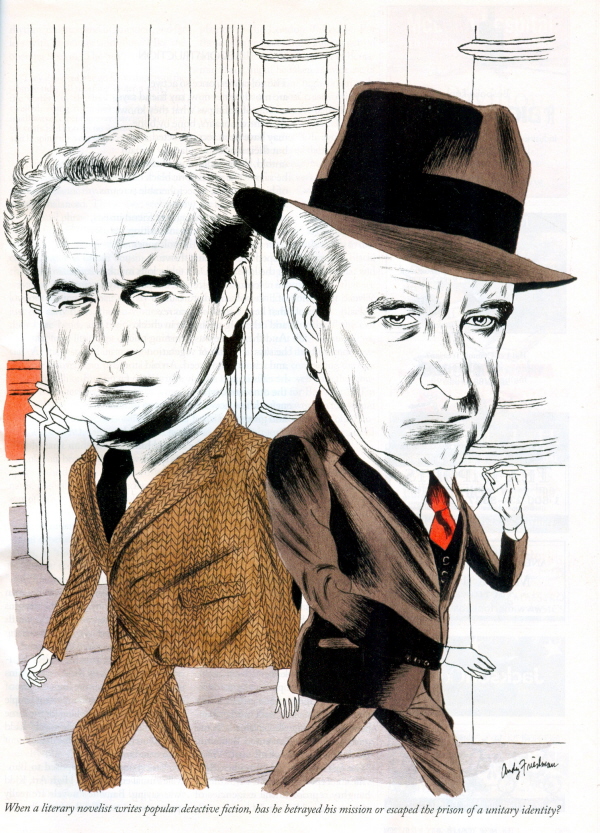

Chính Mình ..... THE CRITICS BOOKS PSEUDONYMOUSLY

YOURS The strange

case of Benjamin Black. Nietzsche

said that the best way to enrage people is to force them to change

their mind

about you. As any author knows, the best way to enrage your publisher

and

offend your critics is to write a novel that differs wildly from your

previous

one. Though a few novelists manage to make versatility their brand,

usually

charges will be laid against you of "incoherence,"

"experimentation," or, even worse, "ambition." To stave off

such remarks, some writers inform their editors, or agents, that they'd

like to

publish under a pseudonym. That generally makes things worse. At first,

the

agents or editors laugh nervously, then they fall back on certain

phrases,

hands in the air: "It's

not ideal," "brand recognition," "the book stores,"

"the horror, the horror." They pour themselves (and perhaps you, too)

a triple Scotch. They beg you to reconsider. And if you have a

reputation they

mutter darkly about not wanting to see you ruin it. If you're

Doris Lessing, or Julian Barnes, or Joyce Carol Oates, or Gore Vidal,

you may

insist nonetheless. The result is a kind of literary bifurcation; a

splitting

of the authorial self Gore Vidal went undercover in the

nineteen-fifties,

winning himself a respite from the homophobic censure he was attracting

at the

time. His pseudonymous incarnation, Edgar Box, delivered three witty

satires

masquerading as detective novels and then was slain. (Vidal also

published work

as Cameron Kay and as Katherine Everard.) In the eighties, Julian

Barnes

briefly partitioned himself: as Barnes, he wrote his earliest novels,

"Metroland" (1980) and "Before She Met Me" (1982) and

"Flaubert's Parrot" (1984); as Dan Kavanagh, he produced sybaritic

detective novels starring a bisexual porn addict called Duffy. This was

less of

a bifurcation than some; the protagonist of "Before She Met Me" was,

at least by the end of the novel, a porn addict, quite as seedy and

murderous

as any of Kavanagh's criminals. The distinction lay mostly in style:

Barnes was

urbane and anecdotal; Kavanagh was lean and to the point. Around the

same time, Doris Lessing decided "to make a little experiment,"

becoming

Jane Somers and publishing a novel called ''The Diary of a Good

Neighbor"

(1983). Lessing wanted "to be reviewed on merit ... to get free of that

cage of associations and labels that every established writer has to

learn to

live inside." Her British publisher, Jonathan Cape, turned Somers down.

The editors at Michael Joseph took her on, saying that she reminded

them a

little of Doris Lessing. Somers's book was published, received mixed

reviews,

and sold only a few thousand copies. Joyce Carol Oates, working as

Rosamond

Smith, sold a psychological mystery, "Lives of the Twins" (1987), to

Simon & Schuster. When all was revealed, Oates's usual editor,

William

Abrahams, at Dutton, was "quite stunned." "I'm her editor and I

should know what she's doing," he said. Rosemont Smith's editor, Nancy

Nicholas, seemed almost to accuse Oates of unfair play: "I signed

'Lives

of the Twins' in good faith as a first nove1." Dragged from her

bolt-hole,

Oates sounded like a plaintiff in the dock, on trial for masquerading

as a

police officer or impersonating someone's long-lost sister. "I wanted

to

escape from my own identity," she said. In these

brand-obsessed days, the author may find herself hanged either way. If

she

comes clean to her editor and agent, they beg or command her to

reconsider. If

not, she gets accused of fraud. And yet nothing could be more

fraudulent than

the idea of a homogeneous oeuvre with a single name attached to it.

"The

authorial persona is a construct, never wholly authentic," Carmela

Ciuraru

writes in the recently published "Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of

Pseudonyms"

(Harper; $24.99). "Never to be yourself and yet always" is how

Virginia Woolf put it. The single authorial self, so consoling to

publishers,

booksellers, and reviewers, can become a mask, clamped onto the authors

face in

such a way that she can no longer remove it. It's like asking any other

person

to stay the same, day after day-always to be her twenty-year-old self,

saying

the same things she said then, in the same way. Life is flux,

Heraclitus said;

existence is change and the self alters at every stage. Proust even

questioned

Christian eternity on these grounds. At the end of a life of constant

transformations, physical and otherwise, who would want to change

permanently

into an unchangeable thing? Wouldn't it be just a trifle boring? This month,

Benjamin Black, the alter ego of the celebrated Irish writer John

Banville,

will release his fifth novel, "A Death in Summer" (Henry Holt; $25).

The birth of Black, according to an interview Banville gave to the

Paris

Review, was sudden, and surprised even his creator. In 2005, just

before the

publication of his novel ''The Sea," which went on to win the Man

Booker

Prize, Banville was staying at a friend's house in Italy. It was March,

the countryside

still furnished with skeletal trees, the opulent spring burgeoning yet

to

begin. Banville hadn't realized at the time that he was great with

child. Then

the labor began: I sat down

at nine o'clock on a Monday morning, and by lunchtime I had written

more than

fifteen hundred words. It was a scandal! I thought, John Banville, you

slut. The first

child of Banville's literary slutting was "Christine Falls" (2006), a

detective noir, starring a pathologist detective called Garret Quirke.

The day

"The Sea" was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, Banville's agent

sent the manuscript of "Christine Falls" to his publisher. "Of

course, everyone tried to persuade me not to use the pseudonym, but I

wanted

people to realize that this wasn't an elaborate postmodernist literary

joke but

the genuine article, a noir novel from Banville's dark brother Benjamin

Black," Banville explained. "It was pure play when I invented

Benjamin Black. It was a frolic of my own." When "The Sea" won

the Man Booker, Banville's acceptance speech contained a haughty

reproof to the

exigencies of commercial publishing: "It is nice to see a work of

art win the Booker Prize." These sounded like the words of a man who

felt

he'd spent years on the margins for his art, but they were also the

words of a

man who had just finished writing his first mystery novel. On the eve

of the

publication of "Christine Falls," Banville's editor, Andrew Kidd, was

at pains to differentiate the book from the rest of Banville's work.

"He doesn’t

want people reading [Black] and looking for the same things they do in

a

Banville novel," Kidd told Reuters. 'With this, his main intent is to

entertain." Entertainment

as opposed to Banville's usual enterprise of High Art, Kidd was saying.

Banville's novels are really prose poems, concerned principally with

rhythm,

cadence, and incantation, and far less with character and plot. Take

the

opening lines of "The Sea": They

departed, the gods, on the day of the strange tide. All morning under a

milky

sky the waters in the bay had swelled and swelled, rising to unheard-of

heights, the small waves creeping over parched sand that for years had

known no

wetting save for rain and lapping the very bases of the dunes. These

sentences are wrought from careful alliteration, with added consonantic

and

asonantic rhymes - every word exactingly balanced. The author seeks out

the

unusual phrase, the original image. In "The Infinities" (2009), he

describes dawn breaking thus: "Many of them sleep on, of course,

careless

of our cousin Aurora's charming matutinal trick, but there are always

the

insomniacs, the restless ill, the lovelorn tossing on their solitary

beds, or

just the early risers, the busy ones, with their knee-bends and their

cold

showers and their fussy little cups of black ambrosia." At its best,

the

incantation works. Banville's novels can become heady and beguiling,

"like

hits of some delicious drug," as one reviewer wrote. Some books you

read

with a sense of creeping unease; they only confirm your isolation, as

if everyone

else were having a conversation you simply can't understand. Other

books

console you, because they draw something up from the depths, something

that resonates.

Banville can really be like this, the sort of writer who, distrustful

of

ordinary modes of expression, locks horns with language in order to

convey

authentic individual experience. "An ordinary day," he writes, in

"Ghosts" (1993). "So I am sitting here at the old pine table, in

that light, with the breakfast things set out and a mug of strong tea

in one hand

and a book in the other and my mind rummaging idly through its own

thoughts." Banville's novels are inquiries into the baroque business of

being in the world, what it feels like to be a mortal, your transient

brain

full of recollections, stories, love for others, and yet never free of

the

sense that everything must vanish in the end. For Banville, this is the

crucial

stuff, and mere mechanisms such as plot are less compelling. At times,

Banville strives so hard for novelty that the enterprise threatens to

collapse

entirely, and, for every reviewer who applauds, there is one who

stifles a

yawn. 'There's lots of lovely language, but not much novel," Tibor

Fischer

complained in the London Telegraph.

For those who've never been able to get on with Banville's work, the

arrival of

Benjamin Black might be taken as evidence of authorial capitulation:

high-flown

style gives way to that most trustworthy and workmanlike of plots, the

detective trail. Where Banville writes, "The cafe. In the cafe. In the

cafe we," or "Oh, agog, agog!," Black writes, "He crossed

the street, dodging a green double-decker bus that parped its horn at

him." Black isn't exactly aiming at stylistic iconoclasm. Occasionally,

he

is even content with cliché. Crossing the border between literary

fiction and

genre fiction, Banville appears, at first glance, to be working to

reinforce

rather than to dissolve that boundary. The birth of Black, he proposes,

is a

generic saturnalia, and the point about a saturnalia is that we know

order will

be restored, that Banville will publish as Banville again. Black is

defined as

the "dark brother," the evil twin- "Banville, you slut." In

interviews, Banville has explained the difference in almost artisanal

terms,

contrasting the ease of writing the Black novels with the

"concentration',

required for Banville: "If I'm Benjamin Black, I can write up to two

and a

half thousand words a day. As John Banville, if I write two hundred

words a day

I am very, very happy." "The

Rogue," as Banville now calls Black, in a piece of presumably playful

schizophrenia,

can certainly hammer out books. In six years, he has produced four

Quirke novels-"Christine

Falls," "The Silver Swan," "Elegy for April," and

"A Death in Summer"-and one, "The Lemur," that doesn't feature

Quirke. Set in nineteen-fifties Dublin, the Quirke novels are riddled

with seediness

and decay. Characters dine on cold and greasy food; they regard their

sallow

faces in cracked mirrors; they endure successive evenings in smoky bars

filled

with volatile, lonely drunks. They stumble home, to their inhospitable,

drafty

flats. Key characters include Malachy, Quirke's brother who is not

quite his

brother, and his daughter, Phoebe, who for years didn't know she was

his

daughter. There is also a shifting cast of self-loathing Irishmen and

faded,

disillusioned women. The novels invariably open with a mysterious

death, Quirke

handily placed in the local morgue, his scalpel revealing the anomaly.

Something doesn't quite add up. Quirke, reluctantly, with a sense that

sleeping

dogs and rotting corpses might best be left to lie, nonetheless finds

he has

been delivered, once again, the itch he cannot scratch. The bar

beckons-can he

swallow enough whiskey to defer the hunt? Alas, though he tries, he

cannot. And

so off he meanders: the classic melancholy, solitary detective,

womanizer, and

alcoholic, peering into the shadows. In "A

Death in Summer," the proprietor of a successful newspaper chain is

found

dead. At first, it is assumed that he has committed suicide, but soon

Inspector

Hackett and Quirke are having the inevitable conversation: "'Are you

saying that what we have here may not be a suicide?' ... They grinned

at each

other, somewhat bleakly." Q1lirke struggles to comprehend the dead

man's

fiery wife, sardonic sister, and disconcertingly calm daughter. He

wanders the

corridors of a vast sterile mansion or two, feeling "like a

stonyhearted

old roué embarrassingly shackled to a lovesick youth," and signals to

successive barmen "to bring the same again." He sinks into despond,

gets "lost in the wilderness." And gradually the mystery is just

about solved. Black is more pragmatic than Banville, more inclined to

use

stereotypes, and his narratives are more often driven by cultural

common denominators,

such as things that are in the news. Where there's a priest, there's

usually a

child-molesting pervert. Other trademarks of the Black oeuvre include:

women,

who are either thin and dangerous or buxom and consoling. (Thin French

women

are particularly troublesome, liable to "glint" when you're least

expecting it.) The smirking English have a penchant for petty crime.

Families,

when not downright incestuous, are fraught with turmoil. Quirke's own

clan is a

feuding mass of pain and guilt; his daughter, Phoebe, is an anxious,

"nun-like"

girl who dresses as if she were in permanent mourning. Quirke isn't

called Quirke

for nothing. He two-times his girlfriend with the wife of a murder

victim,

dallies with the estranged wife of a murder suspect, and has an affair

with

another murder suspect, who is, worse still, an actress. He lies

repeatedly to

the longsuffering Inspector Hackett, he gets drunk, sobers up, goes on

the

wagon, tumbles off the wagon, and generally conducts himself as the

genre requires. Often,

Banville's characters are art historians, or people profoundly

interested in

art, allowing him to interweave painterly images, or anecdotes from the

life of

an artist, with the personal recollections of the protagonist. In ''The

Sea," the symbolically potent painter of the novel is Pierre Bonnard.

In

"Ghosts," it is a fictional painter, Vaublin, "the painter of

absences, of endings. His scenes all seem to hover on the point of

vanishing." In "The Untouchable" (1997), the narrator, Victor

Maskell, is based on Anthony Blunt, the eminent British art historian

who was

uncovered as a Soviet spy. For almost fifty years, Maskell has owned a

(fictional) painting by Nicolas Poussin, ''The Death of Seneca." The

subject of this painting-Seneca accused of conspiracy, and ordered to

commit

suicide, "which he did, with great fortitude and dignity”-is carefully

intertwined

with Maskell's past conspiracy and present public disgrace. The wider

references in Banville are resolutely Western classical and

Mittel-European.

The consultant delivering terminal news in "The Sea" is called Mr.

Todd- Tod is German for

"death"-and the narrator is called Morden (German for "to

murder"). The bed in a mediocre seaside boarding house is "a stately,

high built, Italianate affair fit for a Doge," the headboard

"polished like a Stradivarius." The Greeks proliferate, frequently

strolling

on to amplify a sentiment. In "The Sea," Morden regards himself as a

"lyreless Orpheus." Maskell feels like "Odysseus in Hades, pressed

upon by shades beseeching a little warmth." "The Infinities" is

based on the play "Amphitrion," by the German author Heinrich von

Kleist, though it diverges significantly from, and could be read

without any

knowledge of, the original. Yet the narrative is bulging with classical

allusions: Men have

made me variously keeper of the dawn, of twilight and the wind, have

called me

Argeiphantes, he who makes clear the sky, and Logios, the sweet-tongued

one ...

have conferred on me the grave title Psychopompos, usher of the freed

souls of

men to Pluto's netherworld. For I am Hermes, son of old Zeus and Maia

the

cavewoman. Argeiphantes

does not feature much in the works of Benjamin Black, and you can

imagine Black

knocking back his fourth whiskey of the day, having already churned out

a

couple of thousand words, leaning back in his chair, and saying,

"Banville, you swot." Quirke does have a plaster bust of Socrates in

his flat, but it was given to him as a joke. Yet these

details are not entirely to be trusted, and it would be a little

simplistic to

assume that they prove the distinction between Banville and Black, High

Art and

Pulp Fiction. If you become a bit of a Quirke yourself, and delve

deeper into

Banville's bifurcation, all is not as it seems. As with so many

detective

trails, some of the clues turn out to be red herrings. Saturnalia,

really? Or

is someone trying to put us off the scent? Black's pared-down style is

not

entirely pared down, and, once you look closely, you find that his

narratives

are loaded with poetic devices: "the fleshy heat of him pressing

against

her like the air of a midsummer day thick with the threat of thunder";

'The city seemed bewildered, like a man whose sight has suddenly

failed."

In "A Death in Summer," Quirke starts reading French, sipping claret,

and dreaming of "some sultry impasse beside the

Seine, with swaggering pigeons and water

sluicing cleanly along

the cobbled gutters, half the street in purple shadow and the other

half

blinded by sunlight." He even switches his usual maximum-tar cigarettes

for a packet of Gauloises. Themes and

preoccupations course from Banville to his dark brother, stripped of

some of

their elegant attire, but not transformed completely. Banville's

obsession with

tainted, traumatic childhoods as in "The Sea," "Ghosts,"

and his early novel "Birchwood" (1973)-becomes Black's obsession with

the crime of pedophilia. Banville's obsession with scarcely knowable

origins

becomes, well, Black's obsession with scarcely knowable origins. The

difference

is in emphasis, but these are often sleight-of-hand gestures,

magician's

tricks, making us think that things are substantially different when

really

they are almost the same. Here is Banville on the shifting self "Is the

oldster in his dotage the same that he was when he was an infant

swaddled in

his truckle bed?" Here is Black: "Isn't it strange to think ... that

people who are old now were young once, like us? I meet an old woman in

the

street and I tell myself that seventy years ago she was a baby in her

mother's

arms. How can they be the same person, her as she is now and the baby

as it was

then?" Neither Banville nor Black can escape this sense of

perplexity-about

how we change as we move through time, and how, as Banville writes,

"pieces

of lost time surface suddenly in the murky sea of memory, bright and

clear and

fantastically detailed, complete little islands where it seems it might

be

possible to live, even if only for a moment." Banville's

exploratory monologues owe much to the modernist idea of the

disaffiliated flâneur,

Poe's "man of the crowd," who creeps through the teeming city, or

through the dreamscapes of his own mind, trying to "understand and

appreciate everything that happens," as Baudelaire put it. The

"mainspring

of his genius is his curiosity," Baudelaire added, and this description

could equally describe the average noir detective. Indeed, the

meandering flâneur

and the solitary noir detective have so much in common that they could

even be

dark brothers. Joyce's Leopold Bloom, Chandler's Philip Marlowe,

Borges's

detective Lonnrot, Black's Quirke, and Banville's various narrators all

creep

through their own lives, and the lives of other people, amassing

fragments,

shards of experience, trying to understand something anything - of

death,

disappearance, the past, or why we live and perish, or the bizarreness

of what

we call ordinary life. They share a refusal of the world of "other

people," a sense that exclusion is the only option. To be an

insider-for

flaneurs and detectives, for Banville and for Black-is to be an enemy

or a

fool. Phoebe, Quirke, Maskell, Morden are all fundamentally not at home

in the

world. The narrator of "Birchwood" thinks, "I find the world

always odd, but odder still, I suppose, is the fact that I find it so,

for what

are the eternal verities by which I measure these temporal

aberrations?"

Quirke, opening his front door, "always felt somehow an intruder here,

among these hanging shadows and this silence." In such a world, the

thing

to do is to find an occupation, to distract oneself from the seething

mass of

imponderables. "Let us have a disquisition, to pass the time and keep

ourselves

from brooding," Banville writes, in "Ghosts." Black might

replace "disquisition" with "mystery," but the basic idea

is the same. Banville's half-magical islands and shoddy seaside towns,

Black's

drab Dublin streets are full of perplexing figures, archetypes, as if

the

characters were stalking through some Jungian map of the unconscious:

weakened,

dying fathers, good mothers, bad mothers, twins, "dark doubles,"

ghosts surging up from the past. Bewildering and dreamlike, it doesn't

feel

like home, but where else is there in the end? In the

strange case of Benjamin Black of the author who became another man,

put on

disguises, slipped from one shadow to another-we may start to flounder,

as we

gather the clues, red herrings, fragments, and try to fit them

together. Like

Quirke, like Phoebe, like Banville's narrators, as they keep trying to

"put it all back together ... like a jigsaw puzzle," Black writes.

Or, Banville writes, as they keep "puzzling over the problem: if this

is a

fake, what then would be the genuine thing?" Which is which? Banville

or Black?

High Art or Low Art? Pose or Real Self? What if it's the other way

around? What

if Banville is really Black? So, for years, Black slaved away writing

literary

novels, under the pseudonym John Banville. Of course he could do it;

he's

clever and talented enough to write whatever he likes. Still, he found

it a

strain, sitting there with his thesaurus and his encyclopedia of the

classical

world. He longed for a time when he could give up this literary-fiction

hackwork and write what he really wanted to write. Finally, in 2005,

the moment

came. Such a relief: once he began, he could barely stop. The words

just poured

out. After a few years, he thought, Oh God, better write another of

those

lit-fic novels again, just so they don’t forget all about my dark

brother,

Banville. And so he put his head down, back to two hundred words a day.

Pure

torture. "Never mind," he told himself "Soon I’ll be writing Quirke

again." As Banville

and Black keep telling us, in superficially different ways, things can

"never be complete." Words fail, pretty much everything is pretty

much illusory, and, as Banville writes, in the last lines of

"Birchwood," "some secrets are not to be disclosed under the

pain of who knows what retribution, and whereof I cannot speak, thereof

I must

be silent." Or, as Black writes, in the last lines of “A Death in

Summer”:

Quirke did not reply. How

could he? He did not know the answer." Why did Banville bifurcate?

Perhaps

for money, a good enough reason for anything. Perhaps for fun. Perhaps

as a nod

to the world "of other people," even as he conserves himself as a

rank outsider. Perhaps because he is no literary snob, and knows that

any genre

can produce its classics. Perhaps because he knows that literary

genres,

publishing games, and authorial identities are only half the story, and

that

beneath them somewhere lies the real interest, life itself, the

strangest case

of all .• THE NEW YORKER.

JULY 11 & 18, 2011

|