Ký |

Lẽ dĩ nhiên,

có những bà xấu xa,

nhưng tớ thích những bà xinh đẹp

Ðại triết

gia thất bại trên đường tình Sartre tự đặt

cho mình cái nick, chàng “Don Juan văn học”, a "literary Don Juan",

nhưng thế nhân gọi chàng là thằng khùng mắt lé, a "cross-eyed old

fool." Giai thoại Sartre thấy cua bò trên lưng, Gấu nghe ông anh nhà

thơ kể,

1 lần ngồi Quán Chùa.

Mời độc giả đọc, đích thị lời của anh khùng mắt lé. IN HIS OWN

WORDS Sartre's

Crabs When he was

thirty-two, Jean-Paul Sartre was plagued by a bad case of crabs. As he

told

John Gerassi in 1971:

French

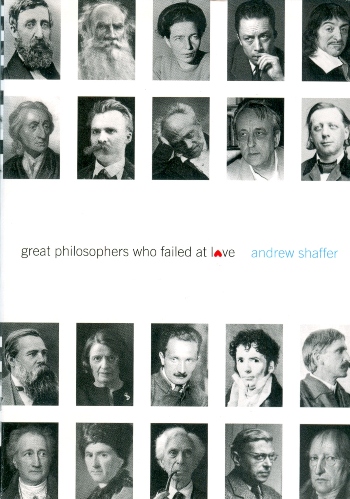

existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre was an unlikely candidate for a

"literary

Don Juan" (as he liked to call himself). The first girl that he became

infatuated with in school rejected him, calling him a "cross-eyed old

fool." It was an inauspicious introduction to the opposite sex. His

prospects did not look any more promising as an adult: He stood just

five-foot-one, dressed in oversized clothes, and had no concept of

personal

hygiene. Sartre

miraculously overcame these deficiencies by simply ignoring them and

projecting

an aura of confidence. He admitted that, as a youth, "[1] was very

melancholy because I was ugly and that made me suffer. I have

absolutely rid

myself of that, because it's a weakness." He only needed one thing to

seduce

women: les mots ("his words"). He lost his

virginity at the age of eighteen to an older married woman. "I did it

with

no great enthusiasm," he said, "because she wasn't very pretty."

It was okay for him to be ugly, but Sartre held the women he slept with

to a

higher standard. In a similar vein, he felt no respect for prostitutes

because

"a girl shouldn't give herself like that" ... yet he regularly

visited brothels with his university friends. When Sartre

was twenty-one, he fell in love with Germaine Marron and requested her

hand in

marriage. Her parents originally consented but called the wedding off

when

Sartre failed his teaching exam in the summer of 1928. "I was

relieved," Sartre wrote. ''I'm not sure of having acted quite correctly

in

this whole affair." In fact, he

had not been acting "correctly" during his engagement: He had been

having an affair with Simone Jollivet, a playwright and actress who

lived in

the nearby city of Toulouse. When Sartre presented Jollivet with a

bottle of

perfume, he was miffed that she placed it on her nightstand beside four

other

bottles from four other lovers. "What? Do you own me?" she said

angrily. "Am I supposed to sit here and wait for your occasional

appearances [in Toulouse]?" After thinking it over,

Sartre agreed with her. "She was right, of course, and I knew it. I

concluded that jealousy is

possessiveness. Therefore, I decided

never to be jealous again." In 1929,

while studying for his second attempt at his teaching certification,

Sartre met

a fellow philosophy student who shared his values: Simone de Beauvoir.

The long

and winding road from their meeting to their burial in a shared

Parisian grave

is recounted earlier in this book (page 31), but suffice it to say that

the

open nature of their relationship allowed Sartre the freedom to sleep

around as

he pleased. His burgeoning literary fame - as a playwright, novelist,

screenwriter, and critic-guaranteed him a constant stream of young

ladies who

were eager to make his acquaintance. Sartre's

love life was not without drama. He often saw several different women

concurrently, booking them into separate slots in his busy schedule.

(It's

amazing that he ever found the time to write.) The details of his

various

liaisons is dizzying, but here's a taste from Hazel Rowley's

Sartre-Beauvoir

biography Tête-à-Tête: His women

all lived within ten minutes of him; they rarely saw one another, and

none of

them knew the truth about his life. Arlette had no idea that after

going for

three weeks' vacation every year with her, Sartre went away with Wanda

for two

or three weeks. Wanda did not know that Sartre still saw Michelle. When

he slept

at Beauvoir's, he told Wanda he was sleeping at home. His letters to

Wanda were

filled with outrageous inventions. He'd be late back to Paris, he once

told

her. He was locked up in a castle in Austria. He continued

to live out his promiscuous dream right up until the end of his life.

In 1979,

at the age of seventy-four, a toothless and blind Sartre remarked to

one of his

girlfriends that, not counting Beauvoir and her girlfriend Sylvie Le

Bon,

"there are nine women in my life at the moment!" Not a bad ending for

a "cross-eyed old fool." IN HIS OWN

WORDS Sartre's

Crabs When he was

thirty-two, Jean-Paul Sartre was plagued by a bad case of crabs. As he

told

John Gerassi in 1971: After I took

mescaline, I started seeing crabs around me all the time. [Three or

four of

them] followed me in the streets, into class. I got used to them. I

would wake

up in the morning and say, "Good morning, my little ones, how did you

sleep?" I would talk to them all the time. I would say, "Okay, guys,

we're going into class now, so we have to be still and quiet," and they

would be there, around my desk, absolutely still, until the bell rang

.... The

crabs stayed with me until the day I simply decided that they bored me

and that

I just wouldn't pay attention to them.

|