|

Note: Bức

hình, trên 1 số NYRB đã cũ, May 1, 2003, tình cờ GNV vớ lại được,

trong

bài viết của Charles Simic, điểm cuốn của Susan Sontag: Nhìn nỗi đau

của kẻ

khác, Regarding the Pain of Others.

Trong bài viết, Simic cũng nhắc đến cái thú của quản giáo Khờ Me Ðỏ,

trước khi làm

thịt ai, thì cho nguời đó được chụp 1 tấm hình làm kỷ niệm. Bài viết

của Simic,

quả đúng là thi sĩ, thật tuyệt. Ông viết về kinh nghiệm ấu thời của

ông, ở vùng

Balkans. Có thể nói, qua bài viết của ông, thì cả lịch sử

nhân loại

được chia ra làm hai, một thời kỳ không có hình, và một, có

hình. Chỉ

khi có hình, thì chúng ta mới được thưởng thức nỗi đau của kẻ khác, dù

không là

chứng nhân tận mắt.

Archives of Horror, Thư Khố, Ảnh Khố của Sự Ghê Rợn, là theo nghĩa đó.

Regarding

the Pain of Others Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 131 pp., $20.00 "the

clarity of everything is tragic" - Witold

Gombrowicz Charles Simic I still have

a memory of a stack of old magazines I used to thumb through at my

grandmother's house almost sixty years ago. They must have dated from

the early

years of the century. There were no photographs in them, just

engravings and

drawings. I was especially enthralled by scenes of battles that were

most

likely depictions of past Balkan wars and rebellions. They were done in

the

heroic manner. The soldiers charged with grim determination through

smoke and

carnage; the wounded hero lay with his chest bared in the arms of his

comrades

seemingly happy as to how things turned out. It was the kind of stuff

that made

me want to play war immediately. I'd run around the house shooting an

imaginary

rifle, crashing down on the floor mortally wounded, then immediately

jumping up

again to fire at the enemy until my grandmother ordered me to stop. Her

nerves

were frayed enough already since there was plenty of real shooting to

be heard

all around us. The year was

1944, the Russian army was closing in on Belgrade, the Germans were

digging in

to fight, while the Americans and the English took turns bombing us. If

one

escaped the city, one was in even greater danger, since a civil war

raged in

the countryside between Communists, royalists, and several other

factions, with

civilians being killed indiscriminately. Like many others, my parents

went back

and forth. Even a six-year-old had numerous opportunities to see dead

people

and be frightened. Still, I made no connection then that I recall,

between what

I saw in those magazines and the things I witnessed in the streets.

That was

not the kind of war I and my friends were playing. This may sound

unbelievable,

but it took war photographs and documentaries that I saw a few years

later to

impress upon me what I had actually lived through. One day when

I was in third or fourth grade our whole class was taken to a museum to

see an

exhibition of photographs of atrocities. The intention, I suppose, was

to show

the youth of a country whose official slogan now was "brotherhood and

unity" what the fascists and their local collaborators had brought

about.

We, of course, had no idea what we were about to see, suspecting that

it would

be something boring, like paintings of our revolutionary heroes. What

we saw

instead were photographs of executions. Not just people hanged or being

shot by

a firing squad, but others whose throats were being cut. Ordinarily, we

took

the opportunity of these class trips to tease the girls and generally

make a

complete nuisance of ourselves, but that day we were mostly quiet. I

recall a photograph

of a man sitting on another man's chest with a knife in his hand,

looking

pleased to be photographed. As

terrifying as the scenes were, they tend to blur in my mind except for

a few

vivid details. A huge safety pin instead of a button on the overcoat of

one of

the victims; a shoe with a hole in its sole that had fallen off the

foot of a

man who lay in a pool of blood; a small white dog with black spots who

stood in

the distance, wary but watching. It was like seeing hard-core

pornographic

images for the first time and being astonished to learn that people did

such

things to one another. I could not talk about this to anybody

afterward;

neither did my schoolmates say anything to me. Our teachers probably

lectured

us afterward about what we saw, but I have no memory of what they said.

All I

know is that I never forgot that day. I suspect

Susan Sontag has written a book others thought of writing but chickened

out of.

The images of war atrocities may seem like a subject about which

there'd be

plenty to say, but somehow it turns out not to be the case. As with

other

all-powerful visual experiences, there's a chasm between what one sees

and what

one can articulate. For instance, I can recall down to its minutest

details Ron

Haviv's close-up photograph taken in 1992 of a Muslim man begging for

his life

on the streets of the town of Beljina in Bosnia. I feel the horror at

what is

about to take place, can even imagine what is being said, know well

enough that

these men with guns are without pity. And yet nothing that I can

imagine or say

equals the palpable reality of this terrified, pleading face on the

verge of

tears. Who is this witness, I ask myself, this photographer who gives

himself

the godlike right to be there? Did he just happen to come along? What

took

place after the camera's click? How come the killers let him go with

the evidence

of their crime? Did they exchange any words before he went his way? Is

it true

then, as Sontag wrote in On Photography (1977), that the camera is a

passport

that annihilates moral boundaries, freeing the photographer from any

responsibility toward the people photographed? If there's anyone

capable of

answering these thorny questions, it is she. As that early book

demonstrated,

she is a most probing critic, one of the very best writers on

photography in

its history. Regarding the Pain of

Others is

a book about photographs without

a single illustration. It begins with a discussion of Virginia Woolf's

Three

Guineas, a book of reflections on the roots of war. In order to test

our

"difficulty of communication," Woolf proposes that we look together

at images of Spanish Civil War atrocities. She wants to know whether

when we

look at the same photographs, we feel the same thing. Sonntag tells us

that

Woolf professes to believe that the shock of such pictures cannot fail

to unite

people of good will: Not

to be pained by these pictures, not to recoil

from them, not to strive to abolish what causes this havoc, this

carnage-these,

for Woolf, would be the reactions of a moral monster. And, she is

saying, we

are not monsters, we members of the educated class. Our failure is one

of

imagination, of empathy: we have failed to hold this reality in mind. Who are the

"we" at whom shock pictures such as these are aimed, Sonntag wonders.

In 1924, Ernst Friedrich published in Germany his Krieg

dem Kriege! (War Against War!), an album of more than 180

photographs drawn from German military and medical archives, almost all

of

which were deemed unpalatable by government censors while the war was

going on,

thinking that circulating them widely would make a lasting impact. As

Sonntag

describes it, the reader gets a photo tour of four years of slaughter

and ruin:

pages of wrecked and plundered churches, obliterated villages,

torpedoed ships,

hanged conscientious objectors, half-naked prostitutes in brothels,

soldiers in

death agonies, corpses putrefying in heaps, close-ups of soldiers with

huge

facial wounds, all of them meant to shock, horrify, and instruct. Look,

the

photographs say, this is what it is like. This is what war does. By

1930, War against War! had gone through ten

editions in Germany and had been translated into many languages.

Judging by the

refinements in cruelty in the next war, its effect was zero. Here's

what Sontag

has to say: The

familiarity of certain photographs builds our

sense of the present and immediate past. Photographs lay down routes of

reference,

and serve as totems of causes: sentiment is more likely to crystallize

around a

photograph than around a verbal slogan. And photographs help

construct-and revise-our

sense of a more distant past, with the posthumous shocks engineered by

the circulation

of hitherto unknown photographs. Photographs that everyone recognizes

are now a

constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares

that it

has chosen to think about. It calls these ideas "memories," and that

is, over the long run, a fiction. Strictly speaking, there is no such

thing as

collective memory-part of the same family of spurious notions as

collective

guilt. But there is collective instruction. All

memory is individual; un-reproducible-it dies

with each person. What is called collective memory is not a remembering

but a

stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it

happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.

Ideologies create

substantiating archives of images, representative images, which

encapsulate common

ideas of significance and trigger predictable thoughts, feelings. I imagine

most of the people carrying out the butchery in Croatia and Bosnia in

the 1990s

had already seen 1 previous photographs of war everything they were now

doing.

In the days of nationalist euphoria that preceded these crimes,

television

audiences all over Yugoslavia were being shown pictures of what one

ethnic

group did to the others in the past. Sontag is right when she points

out that

images of dead civilians serve mostly to quicken the hatred of your

enemy. She

writes: To an

Israeli Jew, a photograph of a child torn apart in the attack on the

Sbarro

pizzeria in downtown Jerusalem is first of all a photograph of a Jewish

child

killed by a Palestinian suicide-bomber. To a Palestinian, a photograph

of a

child torn apart by a tank round in Gaza is first of all a photograph

of a

Palestinian child killed by Israeli ordnance. Looking at

pictures of Serbian atrocities in Croatia, it occurred to me that Serbs

who saw

them may have been envious. They yearned to do the same to Croats.

Today, of

course, Serbs find it difficult to look at photographs of what was done

in

their name. The usual response, as Sontag notes, is that these pictures

must be

fabrications since our brave fighting men are incapable of such

barbarities. It

seems that, for nationalists everywhere, feeling remorseful for the

wrong one

has done to others is a sign of weakness and nothing more. Do

photographs that permit one to linger over a single image make a·

greater

impact on viewers than violence on television and in the movies? Sontag

believes they do, and I agree. The collapse of the World Trade Center

towers on

September 11, 2001, was almost universally described as "unreal,"

"surreal," or "like a movie," and it was. The still images

made by both professional and amateur photographers are at times more

direct

and thus more powerful, as anyone who has seen them will testify. Even

the

death and destruction in the Vietnam War, ·which was documented day

after day

by television cameras and brought to our homes, did not seem to make as

much of

an impression as a few famous photographs of that war did. "Memory

freeze-frames;

its basic unit is the single image," Sontag writes in Regarding the

Pain

of Others. Photographs, her argument runs, seem to have a more innocent

and

more accurate relation to reality, or so we tend to believe. They

furnish

concrete evidence, a way of certifying that such and such did actually

happen. We are more

suspicious of movies and documentaries since we know that they can be

edited to

make a particular aesthetic or political point. Even though the same

can be

done to a photograph, we rarely question what we are seeing. The most

famous

photograph of the Spanish Civil War is a blurred, blackened-white image

of a

Republican soldier shot by Robert Capa's camera at the same moment as

he is

struck by an enemy bullet. The photographer, we think, had the presence

of mind

to point his camera and bear witness and we admire him for it.

"Everyone

is a literalist when it comes to photographs," Sontag writes. It's

disconcerting

to learn from her book that this photo may have been staged, as were

many other

long-familiar war photographs of the past, for reasons of expediency

and

propaganda. Is there a

shame in finding oneself peering at a close-up of some unspeakable act

of

violence? Yes, there is. Can you bear to look at this without

flinching, a

photograph asks, and often we can barely find the strength to do so, as

in the

well-known Vietnam War photograph taken by Huynh Cong Ut, of children

shrieking

with pain and fear as they run away from a village that has just been

doused

with American napalm. What makes it shameful is that the photograph is

not only

shocking, it is also beautiful, the way a depiction of excruciating

torments of

some martyr can be in a painting. "The aesthetic is in reality itself,"

the photographer Helen Levitt once said. One ends up by complimenting

the man

with the camera who not only documents the horror but manages to take a

good

picture. Sontag writes: That

a gory battlescape could be beautiful-in the

sublime or awesome or tragic register of the beautiful-is a commonplace

about

images of war made by artists. The idea does not sit well when applied

to

images taken by cameras: to find beauty in war photographs seems

heartless. But

the landscape of devastation is still a landscape. There is beauty in

ruins....

Photographs tend to transform, whatever their subject; and as an image

something may be beautiful -or terrifying, or

unbearable, or quite bearable-as it is not in real

life. "The

photograph gives mixed signals," Sontag says. "Stop this, it urges.

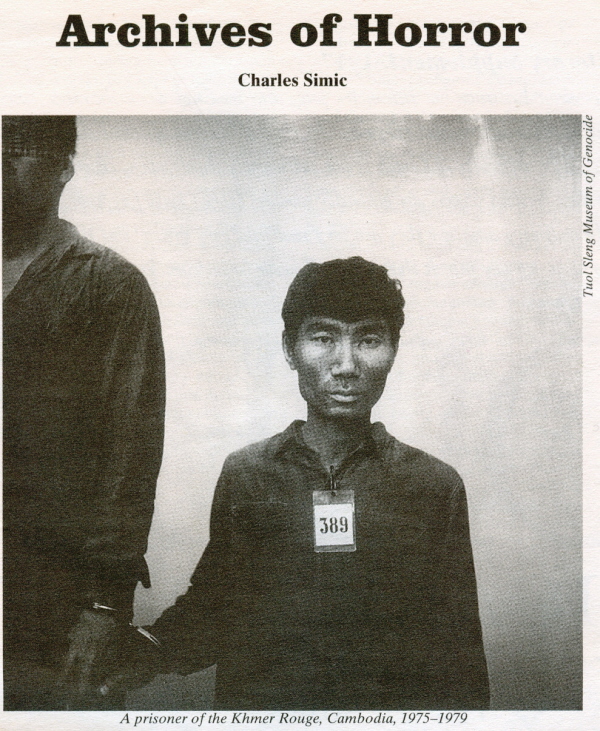

But it also exclaims, What a spectacle!" The Khmer Rouge took thousands

of

photographs between 1975 and 1979 of men and women just before they

were to be

executed. They stare straight at the camera, the number tags pinned to

the top

of their shirts. Their expressions are in turn serious, disbelieving,

worn-out,

and somehow still curious about what comes next. It's hard to meet

their eyes,

while at the same time one can't stop looking at them. We are all

voyeurs,

whether we like or not, Sontag writes, and who could pretend otherwise?

"All suffering people look the same," a friend of mine likes to say.

This is true up to a point, that is, before the camera makes them

distinct. A

little private light bulb that illuminates the life of each of us comes

to be

lit by the photograph. Our memories are dark, labyrinthine museums with

an occasional

properly illuminated image here and there. "Is it

correct to say that people get used to these?" Sontag asks. Are we

better

off for seeing images of atrocities? Do they makes us better people by

eliciting our compassion and indignation so we want to do something

about

injustice and suffering in the world? Finally, are we truly capable of

assimilating what we see? She notes the mounting level of acceptable

violence

and sadism in mass culture, films, television, and video games. Scenes

that

would have had the audiences cover their eyes and shrink back in

disgust forty

years ago are now watched without a blink by every teenager. The same

is true

of the world out there. People can get used to bombs, mass killings,

and other

horrors of warfare. Today I find it hard to believe that I once swiped

a helmet

off a dead German soldier, but I did. Despite what believers in

long-repressed

and buried memories may think, fear and shock unfortunately have

expiration

dates. For every dreadful image I recall, I have forgotten thousands of

others.

In On Photography, Sontag argued that an event known through

photographs after

repeated exposure becomes less real. As much as they create sympathy,

she wrote

then, photographs shrivel sympathy. In her new

book, she's no longer sure. "What is the evidence that photographs have

a

diminishing impact, that our culture of spectatorship neutralizes the

moral

force of photographs of atrocities?" she asks. Our military shares her

uncertainty and has no intention of testing its truth by letting

photographers

roam freely on the battlefield. There are hardly any images of the dead

in the

first Gulf War, mainly stories of wild dogs tearing at the corpses of

the Iraqi

dead. A few pictures slipped past censorship of the war in Afghanistan,

but the

overall policy is to conceal the effects of warfare, especially on

civilians.

The military learned its lesson in Vietnam. "The war itself is

waged," Sontag writes, "as much as possible at a distance, through

bombing, whose targets can be chosen, on the basis of instantly relayed

information

and visualizing technology, from continents away." When local

television

stations begin showing images of civilian casualties we do not hesitate

to bomb

them into silence, as happened in the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia and

with

al-Jazeera in Kabul. "When there are photographs," Sontag-writes, a

war becomes "real." The revulsion at what the Serbs had done in

Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo and the almost universal demand that

something be

done about it were mobilized by images. Unfortunately, as we've seen

with

Cambodia and Rwanda, photographs do not always guarantee

accountability. Still,

a war without pictures, or rather a war sanitized to a few propaganda

images,

is a frightening prospect. Sontag is

rightfully angry with certain French intellectuals fashionable in

academic

circles who speak of "the death of reality" and who assure us that

"reality" is now a mere spectacle. "It suggests, perversely,

usuriously,"

she writes, "that there is no real suffering in the world." And yet,

there was a time when she was somewhat inclined toward that view, when

she was

tempted to say that it is images and not reality that photography makes

accessible.

She charged photography of doing as much to deaden conscience as to

arouse it,

and she was not wrong. "Photography implies," she wrote, "that

we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it. But

this is

the opposite of understanding, which starts from not accepting the

world as it

looks." Some reviews of the new book I have seen claim that she has now

repudiated this view. This simplifies her ideas in the earlier book

about the

relationship of the image world to the real one which are not only more

nuanced, but are also mindful of the long history of that question

going back

to Plato. By insisting that there is indeed such a thing as reality, it

does

not mean that she now embraces a reductive, either / or approach with

truth and

beauty as irreconcilable opposites. Lastly, it's not photographs of

bell

peppers, nudes, or the Grand Canyon that are her subject here, but

rather what

she once called "the slaughter-bench of history." Timely as it

is, Sontag's extended meditation on the imagery of war in Regarding

the Pain of Others is guaranteed to make some readers

uneasy. These are things they'd rather not dwell on. Consumers of daily

violence, she knows, are schooled to be cynical about the temptation of

strong

feelings. Her book on the other hand bristles with indignation. She has

no patience

for those who are perennially surprised that depravity exists, who

change the

subject when confronted with evidence of cruelties humans inflict upon

other

humans. "No one after a certain age," she goes on to say, "has

the right to this kind of innocence, of superficiality, to this degree

of

ignorance, and amnesia." Sontag is a

moralist, as anyone who thinks about violence against the innocent is

liable to

become. The time she spent in Sarajevo under fire gives her the

authority. Most

of us don't understand what people go through, she writes. True, we

only have photographs.

Even if they are only tokens, they still perform a vital function,

Sonntag

insists. They certainly do for me. Like the one by Gilles Peress I saw

some

years ago of a child with eyes bandaged being led by his mother down a

busy

street in Sarajevo. Or another, by the same photographer, where we see

a man in

a morgue approach three stretchers with bodies lying on them and cover

his face

as he recognizes a friend or a relative. The morgue attendant is

expressionless

as he stands watching. Men and

women who find themselves in such circumstances, one says to oneself,

do not

have the luxury of patronizing reality. Such photographs preserve,

however tenuously, the mark of some person's suffering in the great

mass of

faceless and anonymous victims. We ought to be grateful to Susan Sontag

for

reminding us of this. If photography is a form of knowledge, writting

about it

with critical discernment and passion, as she does, is bound to make

trouble

for every variety of intellectual and moral smugness. +

|