|

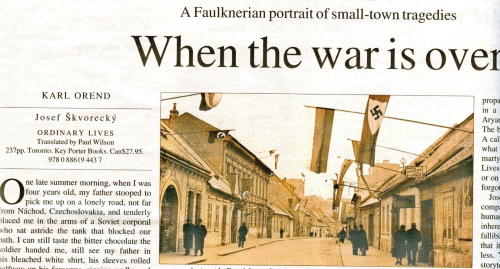

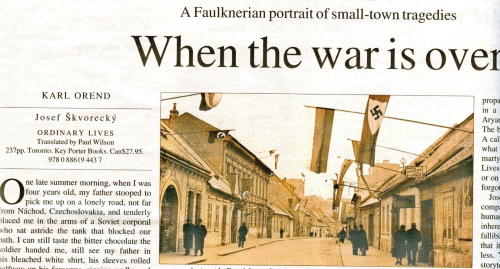

Khi chiến tranh kết thúc

Trong

Stranger Shores, tập

tiểu luận, [1986-1999] nhà văn nhớn, nhà phê bình nhớn, nhà văn Nobel,

Coetzee đi

một đường

ai điếu hơi bị sớm nhà văn hiện còn sống, Josef Skvorecky: … Looking

back over his career, Skvorecky produces a humorously modest obituary:

“After

years of socialism… he was..”. [Nhìn lại sự nghiệp văn

chương....

]. Không

biết ông nhà văn này có

quê không, nhưng mới đây, cho ra lò một cuốn thật hách xì xằng [xb năm

2004, bản dịch tiếng Anh, 2009], tờ

TLS, số

mới nhất đi một đường chào mừng: Josef Škvorecký's Ordinary

Lives A novel

that reveals the

horror inherent in life under totalitarianism, trong

đó để nhẹ nhà phê bình

nhớn, Nobel văn chương một câu: In

2002, in Stranger Shores,

J. M. Coetzee published a premature obituary on Škvorecký’s literary

career,

implying he was finished as a writer.

Chính là do đọc bài viết của Coetzee, chê thật nặng

nề, mà Gấu bỏ qua ông này, cho tới khi đọc bài viết trên TLS số mới

nhất, thì mới ngã ngửa ra rằng, ông, cũng công dân Canada, cũng cư dân

Toronto như Gấu, và, cũng mê Faulkner, như Gấu, tuy nhiên, đã từng là

ứng viên Nobel văn chương, chưa kể cả lô giải thưởng này nọ.

Xin

giới thiệu một bài viết,

từ website của ông. Tin Văn sẽ dịch bài này, tặng mấy đấng VC nằm vùng,

"mấy thằng ngu có ích", "mấy đứa con nít không hề biết đùa với lửa có

khi mang họa, cho tới khi

lửa đốt rụi ngôi nhà Miền Nam

của chúng!"

They are — if you'll excuse the platitude — like a child who doesn't

believe

that fire hurts, until he burns himself.

Bài

trên TLS vinh danh Josef,

nhiều câu tuyệt cú mèo, như để bù lại cho tác giả về những bất công mà

Coetzee đối xử với ông

A REVOLUTION IS

USUALLY THE

WORST SOLUTION

Cách Mạng là giải

pháp khốn

kiếp nhất, thường là như vậy!

In

October 1981 Skvorecky participated in an

international conference held in Toronto,

on the subject of "The Writer and Human Rights". The participants

included Margaret Atwood, Stanislaw Bardnczak, Joseph Brodsky, Allen

Ginsberg,

Nadine Gordimer, Susan Sontag, Michel Tournier, and many others.

Skvorecky's

speech was a disturbing reminder that "human rights" can be and have

been abused by regimes of the left as well as of the right. To some

left-leaning

members of the audience, it was not what they had come to hear.

FRANKLY, I FEEL

frustrated

whenever I have to talk about revolution for the benefit of people who

have

never been through one. They are — if you'll excuse the platitude —

like a

child who doesn't believe that fire hurts, until he burns himself. I,

my

generation, my nation, have been involuntarily through two revolutions,

both of

them socialist: one of the right variety, one of the left. Together

they

destroyed my peripheral vision. When I was fourteen, we were told at

school

that the only way to a just and happy society led through socialist

revolution.

Capitalism was bad, liberalism a fraud, democracy bunk, and

parliamentarism

decadent. Our then Minister of Culture and Education, the late Mr.

Emanuel

Moravec, taught us this, and then sent his son to fight for socialism

with the

Hermann Goering SS Division. The son was later hanged; the minister, to

use

proper revolutionary language, liquidated himself with the aid of a gun.

When I was twenty-one, we

were told at Charles

University

that the only

way to a just and happy society led through socialist revolution.

Capitalism

was bad, liberalism a fraud, democracy bunk, and parliamentarism

decadent. Our

then professor of philosophy, the late Mr. Arnost Kolman, taught us

this, and

then gave his half-Russian daughter in marriage to a Czech Communist

who fought

for socialism with Alexander Dubcek. Later he fled to Sweden.

Professor Kolman, one of the very last surviving original Bolsheviks of

1917

and a close friend of Lenin, died in 1980, also in Sweden.

Before his death, he

returned his Party card to Brezhnev and declared that the Soviet Union had betrayed the socialist

revolution. In 1981 I am told by

various people who suffer from Adlerian and Rankian complexes that the

only way

to a just and happy society leads through socialist revolution.

Capitalism is

bad, liberalism a fraud, democracy bunk, and parliamentarism decadent.

Dialectically, all this makes me suspect that capitalism is probably

good,

liberalism may be right, democracy is the closest approximation to the

truth,

and parliamentarism a vigorous gentleman in good health, filled with

the wisdom

of ripe old age.

There have been quite a few

violent revolutions in our century, most of them Communist, some

Fascist, and

some nationalistic and religious. The final word on all of them comes

from the

pen of Joseph Conrad, who in 1911 wrote this in his novel Under Western

Eyes:

...in a real revolution — not

a simple dynastic change or a mere reform of institutions — in a real

revolution the best characters do not come to the front. A vio- lent

revolution

falls into the hands of narrow-minded fanatics and of tyrannical

hypocrites at

first. Afterwards comes the turn of all the pretentious intellectual

fail- ures

of the time. Such are the chiefs and the leaders. You will notice that

I have

left out the mere rogues. The scrupulous and the just, the noble,

humane, and

devoted natures; the unselfish and the intelligent may begin a movement

— but

it passes away from them. They are not the leaders of a revolution.

They are

its victims: the vic- tims of disgust, of disenchantment — often of

remorse.

Hopes grotesquely betrayed, ideals caricatured — that is the definition

of

revolutionary success. There have been in every revolution hearts

broken by

such successes.

I wonder if anything can be

added to this penetrating analysis? The scenario seems to fit

perfectly. Just

think of the Strasser brothers, those fervent German nationalists and

socialists:

one of them liquidated by his own workers' party, the other having to

flee,

first to capitalist Czechoslovakia,

then to liberal England,

while their movement passed into the hands of that typical

"intellectual

failure", the unsuccessful artist named Adolf Hitler. Think of Boris

Pilnyak, liquidated while those sleek and deadly scientific bureaucrats

he

described so well — who were perfectly willing to liquidate others to

bolster

their own careers — bolstered their careers, leaving a trail of human

skulls

behind them.

Think of Fidel Castro's

involuntary volunteers dying with a look of amazement on their faces in

a

foreign country where they have no right to be, liquidating its black

warriors

who for years had been fighting the Portuguese. Think of the German

Communists

who, after the Nazi Machtübernahme (the grabbing of power), fled to Moscow and then,

broken-hearted, were extradited back into the hands of the Gestapo

because

Stalin honoured his word to Hitler; the Jews among them were designated

for

immediate liquidation, the non-Jews were sent to Mauthausen and

Ravensbrück.

It is all an old, old story.

The revolution — if you don't mind another cliché — is fond of

devouring its

own children. Or, if you do mind, let me put it this way: the

revolution is cannibalistic.

It is estimated that violent Communist revolutions in our century have

dined on

about one hundred million men, women, and children. What has been

gained by

their sumptuous feast? Basically two things, both predicted by the

so-called

classics of Marxism-Leninism: the state that withered away, and the New

Socialist Man.

The state withered away all

right — into a kind of Mafia, a perfect police regime. Thought-crime,

which

most believed to be just a morbid joke by Orwell, concocted when he was

already

dying of tuberculosis, has become a reality in today's "real

socialism", as the stepfathers of the Czechoslovak Communist Party have

christened their own status quo. The material standards of living in

these

post-revolutionary police states are invariably lower, often much

lower, than

those of the developed Western democracies. But of course, the New

Socialist

Man has emerged, as announced.

Not quite as announced. Who

is he? He is an intelligent creature who, sometimes in the interest of

bare survival,

sometimes merely to maintain his material living standards, is willing

to

abnegate the one quality that differentiates him from animals: his

intellectual

and moral awareness, his ability to think and freely express his

thought. This

creature has come to resemble the three little monkeys whose statuettes

you see

in junk shops: one covers its eyes, another its ears, the third its

mouth. The

New Socialist Man has thus become a new Trinity of the

post-revolutionary age.

Therefore, with Albert Camus,

I suspect that in the final analysis capitalist democracy is to be

preferred to

regimes created by violent revolutions. I must also agree with Lenin

that those

who, after the various gulags (and after the Grand Guignol spectacle of

the

Polish Communist Party exhorting the Solidarity Union to shut up or

else the

Polish nation will be destroyed — and guess who will destroy it), still

believe

in violent revolutions are indeed "useful idiots".

In the Western world, such

mentally retarded adults sometimes point out, in defence of violence,

that

capitalism is guilty of similar crimes. Most of these crimes, true,

have

occurred in the past, often in the distant past, but some are happening

in our

own time, especially in what is known as the Third

World.

But to justify crimes by arguing that others have also committed them

is, to

put it mildly, bad taste. To exonerate the Communist inquisition by

blaming the

Catholic Church for having done the same thing in the Dark Ages amounts

to an

admission that Communism represents a return to the Dark Ages. To

accuse

General Pinochet of torturing his political prisoners, and then barter

your own

political prisoners, fresh from psychiatric prison-clinics, for those

of

General Pinochet is—shall we say—a black joke.

Does all this mean that I

reject any violent revolution anywhere, no matter what the

circumstances are? I

have seen too much despair in my time to be blind to despair. It's just

that I

do not believe in two things. First, I do not think that a violent

uprising

born out of "a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing

invariably

the same object" which "evinces a design to reduce" men

"under absolute despotism" should be called a revolution; because

when such a revolution later produces another "long chain of abuses and

usurpation" and people rise against it, to be linguistically correct we

would have to call such an uprising a "counter-revolution". In our

society, however, this term has acquired a pejorative meaning it does

not

deserve.

Second, I do not believe that

any violent revolution in which Communists or Fascists participate can

be

successful, except in the Conradian sense as quoted above. Because,

quite

simply, I do not trust authoritarian ideologies. Every revolution with

the participation

of Communists or Fascists must eventually of necessity turn into a

dictatorship

and, more often than not, into a state nakedly ruled by the police.

Neither

Fascists nor Communists can live with democracy, because their ultimate

goal,

no matter whether they call it das Führerprinzip or the dictatorship of

the

proletariat, is precisely the "absolute despotism" of which Thomas

Jefferson spoke. They tolerate partners in the revolutionary effort

only as

long as they need them to defeat the powers that be — not perhaps

because all

Communists and Fascists are radically evil but because they are

disciplined

adherents of ideologies which command them to do so, since that is what

Hitler

or Lenin advised. The Fascists are more honest about it: they say

openly — at

least the Nazis did — that democracy is nonsense. Lenin was equally

frank only

in his more mystical moments; otherwise the Communists use Newspeak.

But as

soon as they grow strong enough, they finish off democracy just as

efficiently

as the Fascists, and usually more so.

All this is rather abstract,

however, and since individualistic Anglo-Saxons usually demand

concrete,

individual examples, let me offer you a few. In Canada

there lives an old professor

by the name of Vladimir Krajina. He teaches at the University

of British Columbia in Vancouver and is

an

eminent botanist who has received high honours from the Canadian

government for

his work in the preservation of Canadian flora. But in World War II, he

was

also a most courageous anti-Nazi fighter. He operated a wireless

transmitter by

which the Czech underground sent vi- tal messages to London,

information collected by the members

of the Czech Resistance in armament factories, by "our men" in the

Protectorate bureaucracy who had access to Nazi state secrets, and by

Intelligence Service spies such as the notorious A-54. The Gestapo, of

course,

was after Professor Krajina. For several years, he had to move from one

hideout

to another, leaving a trail of blood behind him, of Gestapo men shot by

his co-fighters,

of people who hid him and were caught and shot. After the war, he

became an MP

for the Czech Socialist party. But his incumbency lasted for little

more than

two years. Immediately after the Communist coup in 1948, Professor

Krajina had

to go into hiding again, and he eventually fled the country.

Why? Because the Communists

had never forgotten that he had warned the Czech underground against

cooperating with the Communists. And he was right: he was not the only

one to

flee. Hundreds of other anti-Nazi fighters were forced to leave the

country,

and those who would not or could not ended up on the gallows, in

concentration

camps, or, if they were lucky, in menial jobs. Among them were many

Czech RAF

pilots who had distinguished themselves in the Battle of Britain and

then had

returned to the republic for whose democracy they had risked their

lives. All

this is a story since repeated in other Central and East European

states. It is

still being repeated in Cuba,

in Vietnam, in Angola, and most recently in Nicaragua.

In a recent article in the

New York Review of Books, V. S. Naipaul tells about his experiences in

revolutionary Iran.

He met a Communist student there who showed him snapshots of Communists

being

executed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards and then told him about

his love

for Stalin: "I love him. He was one of the greatest revolutionaries....

What he did in Russia

we

have to do in Iran.

We, too, have to do a lot of killing. A lot.... We have to kill all the

bourgeoisie." For what purpose? To create a Brezhnevite Iran, perhaps?

To

send tens of thousands of new customers to the Siberian Gulag? But

obviously

the bourgeois don't count. They were useful when they fought the shah,

as the

Kadets had been in 1917 while they fought the czar. Now they are

expendable.

They have become "Fascists", just like the Barcelonian anarchists

denounced in the Newspeak of the Communist press decades ago in Spain, as described by Orwell in Homage

to Catalonia.

They have

become nonpeople. James Jones once wrote, "It's so easy to kill real

people in the name of some damned ideology or other; once the killer

can

abstract them in his own mind into being symbols, then he needn't feel

guilty

for killing them since they're no longer human beings." The Jews in Auschwitz, the zeks in the Gulag, the

bourgeoisie in a

Communist Iran. Symbols, not people. Revolutionsfutter.

When Angela Davis was in

jail, a Czech socialist politician, Jiri Pelikan, a former Communist

and now a

member of the European Parliament for the Italian Socialist Party,

approached

her through an old American Communist lady and asked her whether she

would sign

a protest against the imprisonment of Communists in Prague. She agreed to do so, but not

until

she got out of jail because, she said, it might jeopardize her case.

When she

was released, she sent word via her secretary that she would fight for

the

release of political prisoners anywhere in the world except, of course,

in the

socialist states. Anyone sitting in a socialist jail must be against

socialism,

and therefore deserves to be where he is. All birds can fly. An ostrich

is a

bird. Therefore an ostrich can fly. So much for the professor of

philosophy

Angela Davis.

So much for concrete

examples.

In his Notebooks, Albert

Camus recorded a conversation with one of his Communist co-fighters in

the

French Resistance: "Listen, Tar, the real problem is this: no matter

what

happens, I shall always defend you against the rifles of the execution

squad.

But you will have to say yes to my execution."

Evelyn Waugh, whom I confess

I prefer to all other modern British writers, said in an interview with

Julian

Jebb, "An artist must be a reactionary. He has to stand out against the

tenor of the age and not go flopping along; he must offer some little

opposition."

All I have learned about

violent revolutions, from books and from personal experience, convinces

me that

Waugh was right.

Nguồn

|

|