|

Nikolai Gogol DEAD SOULS Translated by

Donald Rayfield; illustrated by Marc Chagall 366pp. Garnett Press. £29.99.

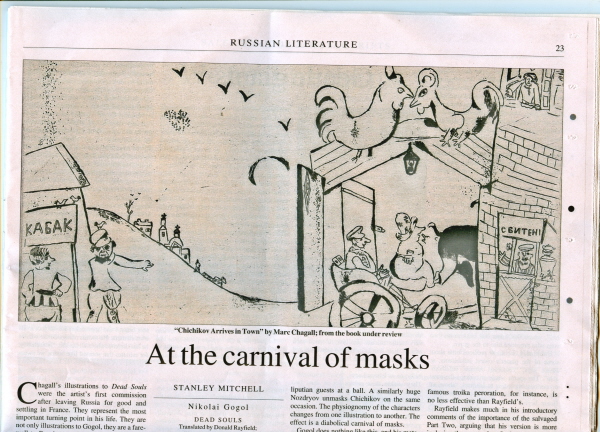

978095358 787 8 Chagall's

illustrations to Dead Souls were the artist's first

commission after leaving This is

the first edition of Dead Souls to include all

Chagall's

illustrations since their original appearance in The

illustrations marked a

new direction for Chagall. With the one exception, an earlier

experiment in

autobiography, he was etching for the first time, searching exuberantly

for new

techniques that ranged from drypoint to aquatint. To quote from Marx in

a

different context: all that is solid melts into air. When Chichikov

visits the

landowner, Manilov, the two men are done in aquatint and look

relatively human.

When they part, their bodies become transparent, as if they are

themselves the

dead souls. Magnitudes vary crazily and the humor is magnificent. A

monstrous

Sobakevich prepares to settle into a diminutive armchair. The clerks in

the

court office are reduced to tiny heads, wielding matchstick pens at

barely

visible desks, or faces floating in a void. A giant condescending

Chichikov

appears before the Lilliputian guests at a ball. A similarly huge

Nozdryov unmasks

Chichikov on the same occasion. The physiognomy of the characters

changes from

one illustration to another. The effect is a diabolical carnival of

masks.

Gogol does nothing like this, and his metaphorical flights are by

comparison

realistic. For this reason, a commentary on the relationship of the

images to

the text would have been welcome. Gogol himself refused any request to

illustrate

his work, commenting that any illustration could only "sweeten" the

novel.

In his short introduction, Donald Rayfield claims that Gogol found in

Chagall

his true illustrator, calling Chagall's imagination "surreal". Yet in

his comments on the novel, Rayfield sides with the nineteenth-century

"realist"

interpretations. Gogol's characters, he suggests, are alive and well in

today's Rayfield

makes much in his

introductory comments of the importance of the salvaged Part Two,

arguing that

his version is mort inclusive than any other. In fact, Christophel

English's

translation (1987) includes both the stories that Rayfield misses in

earlier

translations. More importantly, Rayfield suggest that Part Two

prefigures the

novels of Goncharov, Turgenev, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. Since Part Two

sets out

on the road of redemption, where we behold a freshly burnished

Chichikov,

accompanied by figures who on the whole are less imaginative than those

in Part

One, we are unlikely to find the future Russian literature germinating

here.

Nor can I imagine Chagall wanting to illustrate Part Two. Nikolai

Dobrolyubov

spotted the only convincing connection between Part Two and later

Russian

fiction in his essay What is Oblomovvism?

(1859-60), where he linked the landowners Tentetnikov and Platonov with

Gonchaarov's hero, Oblomov. But in Part One, Gogol had already

characterized an

idle dreamer in Manilov who is much more perniciously comic than this

pair. The

famous remark often attributed to Dostoevsky that "We all emerged from

Gogol's overcoat" (a reference to Gogol's story of 1842) remains more

accurate. TLS

JULY 10 2009 |