|

Thieves must sit in prison Trộm

cướp phải ngồi trong nhà tù. Alternately Putin OWEN

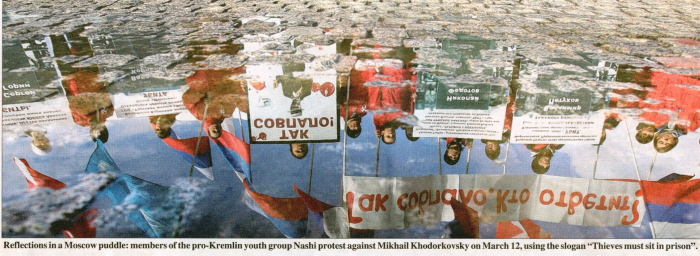

MATTHEWS In The Age of Assassins, Yuri Felshtinsky and Vladimir Pribylovsky follow the fortunes of the KGB and its successor, the FSB, over the past forty years of Soviet and Russian history. They argue that Putin is just the latest and most powerful in a succession of secret police thugs who have always, to a greater or lesser extent, been Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky have dug out a wealth of detail on the rise of Putin, from his days as deputy mayor of St Petersburg, where they claim he was "deeply involved in organised crime", to his lucky break in 1999 when Boris Berezovsky, arch-oligarch and friend of the Yeltsin "family", promoted Putin as a supposedly uncontroversial successor to Yeltsin. They also trace the rise of the FSB as Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky assemble an impressive array of evidence to suggest FSB involvement in the bombings; indeed, Felshtinsky wrote a book with Litvinenko on the same subject (Blowing Up Russia, 2007). But too many loose ends are left dangling to make the case really stick. One is the crucial evidence of Colonel Mikhail Trepashkin of the FSB, who claimed that one of the bombers was his fellow FSB officer Vladimir Romanovich. Trepashkin was subsequently imprisoned and Romanovich apparently murdered - but that alone doesn't make Trepashkin's allegations true. The Age of Assassins is competent and convincing as it catalogues a series of crimes and misdemeanours perpetrated by Putin and the FSB, from institutional corruption and political trials to stifling the free press and appointing a psychopath to rule Michael Stuermer's book is written in an entirely different key. Stuermer is a distinguished German political historian and r journalist; he is also one of the Kremlin's favoured Stuermer frequently undermines his academic rigour with lapses into fatuity. He opines that At times, it is hard to believe that these two books are about the same man. Stuermer claims that it was the KGB's "almost unlimited access to untainted information" that attracted "the ambition, patriotism and efforts of Vladimir Putin", suggesting that Putin's application to join the KGB was driven by intellectual curiosity. Felshtinsky and Pribyylovsky describe, in painful detail, just how cynical, money-grubbing and violent that KGB elite was in practice: "Russia became a corporate republic ... a corporation took over the government of the country and put its own President in charge", In Stuermer's account, Putin is, a master strategist bent on rebuilding his nation's lost prestige, and in the process discarding the debris of Yeltsin's failed experiment with democracy. In Felshtinsky and Pribylovsky's, he is the head of a criminal gang devoted to enriching itself and eliminating any challenge to its authority. Stuermer sees Putin from outside and above, a major player on the world geopolitical stage. Felshhtinsky and Pribylovsky see Putin from inside and below, tracing the theft, scheming and killing that surrounded his rise, and the ruthlessness, hypocrisy and fear that have accompanied the undoubted stability and wealth of his years in power. Can both be right? TLS 27 Tháng Ba 2009

|