|

Happy

Birthday & Holidays Fri, March

11, 2011 9:18:27 AM Richie I

miss u too much Phạm Công Thiện qua đời, thọ 71 tuổi Nhà văn, nhà thơ, nhà tư

tưởng, dịch giả, giáo sư, cư sĩ Phật giáo Phạm Công Thiện vừa qua đời

ngày 8

tháng 3 năm 2011 tại Houston,

Hang Son Doong

Ed. Alfred

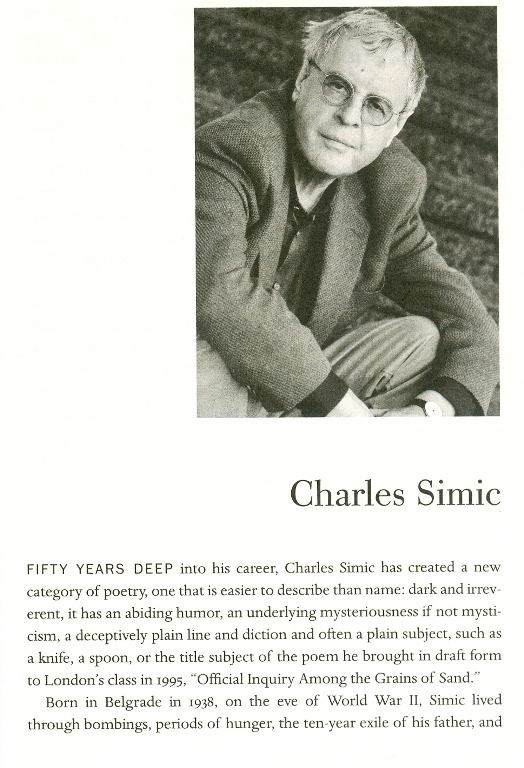

A. Knopf, NY, 2010 FIFTY YEARS

DEEP into his career, Charles Simic has created a new category of

poetry, one

that is easier to describe than name: dark and irreverent, it has an

abiding

humor, an underlying mysteriousness if not mysticism, a deceptively

plain line

and diction and often a plain subject, such as a knife, a spoon, or the

title

subject of the poem he brought in draft form to London's class in 1995,

"Official Inquiry Among the Grains of Sand." Born in

Belgrade in 1938, on the eve of World War II, Simic lived through

bombings,

periods of hunger, the ten-year exile of his father, and the

imprisonment of

his mother. "Hitler and Stalin conspired to make me homeless," he has

said. Not until he was in his mid-teens was his family reunited,

settling in

the United States. Simic began writing poetry as a high school student

in the

Chicago suburbs. One aim of

his poetry, Simic says, is "to restore strangeness to the most familiar

aspects of experience." To London he says that "the foundation of

poetry is based on chance," and as chance can run toward violence,

violence, too, is at an edge not far away. "Official Inquiry" and its

grains of sand run together with a snooping seagull of "a secret

government agency." But even as Simic describes line by line the making

of

the poem, he laughs when London suggests that he might have an overall

vision.

"No. No, I never had a vision," he says. "Sometimes awkwardness

is inevitable and important." Simic was

still making "Official Inquiry Among the Grains of Sand" at the time

of his visit. "Here's a little poem I'm working on," he wrote to her

weeks earlier. "This draft will change, so I'll have another version

when

I come." The poem eventually appeared in his 1996 volume, Walking

the Black Cat, a National Book

Award finalist and one of five books of poetry he published in the

1990S.

Simic, who has taught at the University of New Hampshire since 1973,

became the

U.S. poet laureate in 2007. Năm mươi năm

ăn nằm với thơ, Charles Simic đã tạo ra một thể loại thơ, mới, dễ miêu

tả hơn

là đặt tên cho nó: u tối, thiếu sự tôn kính, thường xuyên tưng tửng, bí

ẩn “chìm”,

nếu không muốn nói, thần bí; dòng thơ bằng phẳng đánh lừa người đọc;

lời phán,

và đề tài thường giản dị, như con dao, cái thìa, hay như tít bản nháp

bài thơ

mà ông mang vô lớp cho London coi, vào năm 1955: “Một cuộc điều tra

chính thức

giữa những hạt cát” Sinh tại

Belgrade 1938, đêm trước Đệ Nhị Chiến, Simic ‘đau đáu’ kinh qua bom

đạn, đói khát,

và 10 năm lưu vong của ông già và bà mẹ đi tù. “Hitler và Stalin, hai

thằng khốn

này đã âm mưu làm cho tôi thành 1 kẻ không có nhà ở”, ông đã từng nói.

Phải đến

khi ông được 15, 16 tuổi thì gia đình mới được đoàn tụ, và tái định cư

ở Mẽo. Thơ tôi nhắm

tái lập lại cái “kỳ kỳ cho hầu hết những sắc thái quen thuộc của kinh

nghiệm”. “Cơ

bản của thơ dựa trên cơ may, tình cờ”, và bởi vì cơ may thường chạy tới

bạo động,

thành thử bạo lực thì cũng ngay mép bờ, chẳng ở đâu xa. Và mặc dù ông

làm thơ từng

dòng, từng dòng, khi được hỏi, liệu ông có 1 viễn ảnh lớn, bao trùm lên

nó, nhà

thơ lắc đầu. Nô, tớ chẳng bao giờ có một viễn ảnh. “Đôi khi, cái sự lớ

ngớ thì

không thể tránh được, và nó thì quan trọng”

The New

American Pessimism

Charles Simic  A protester at a march and rally at the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison, March 5, 2011 I can’t remember

when I last heard someone genuinely optimistic about the future of this

country. I discount politicians, investment bankers and generals since

their

line of work requires that they offer upbeat assessments of everything

from our

deteriorating economy to our suicidal wars, and assorted narcissists

accustomed

to shutting their eyes to the plight of their fellow Americans. The

outright

prophets of doom and gloom among our friends and acquaintances tended

to be a

rare breed until recently. They were mostly found among the elderly,

whose

lives had an inordinate share of tragedies and disappointments, so one

didn’t

take their bleak outlook as applicable to the rest of us. One

encountered

inveterate optimists, idealists, or even Niebuhrian realists in the

past; now,

one finds people of all ages and backgrounds eager to tell you how

screwed up

everything is, and, on a more personal note, what a difficult time they

are

having—not just making ends meet, but understanding why the country

they

thought they knew has become unrecognizable. Just look at the assault on the rights of state workers that Wisconsin’s new governor Scott Walker and a group of state senators have rammed through a rump legislature without any debate. The same approach is now spreading to several other states in the heartland. In the new USA, teachers, union workers, women, children, the unemployed and the hopeless are the cause of unsustainable deficits, and a dog-eat-dog philosophy that is supposed to make us great again prevails. It must be

difficult for any hostess nowadays to stop her dinner guests from

reciting to

each other over the course of an evening the endless examples of lies

and

stupidities they’ve come across in the press and on TV. As they get

more and

more wound up, they try to outdo each other, losing all interest in the

food on

their plates. I know that when I get together with friends, we make a

conscious

effort to change the subject and talk about grandchildren, reminisce

about the

past and the movies we’ve seen, though we can’t manage it for very

long. We end

up disheartening and demoralizing each other and saying goodnight,

embarrassed

and annoyed with ourselves, as if being upset about what is being done

to us is

not a subject fit for polite society. In an atmosphere of growing anxiety and hysteria, in which the true causes and the scale of our dire national predicament are deliberately concealed and obfuscated by our political establishment and by the corporate media, no wonder there’s confusion and anger everywhere. As anyone who has traveled around this country and talked to people knows, Americans are not just badly informed, but downright ignorant about most things that affect their lives. How nice it would be if our President leveled with us and told us that our deficit is caused in significant part by the wars we are fighting in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the hundreds of military bases we are maintaining around the world, the huge tax breaks for the rich, and the bailout of Wall Street. As we know, we are not about to hear anything of the kind. By the

president’s calculation, telling the truth to the American people would

doom

his reelection campaign, since he would not be able to raise the

billion

dollars he needs this time around. The kind of people who have that

kind of

money and will agree to contribute to his campaign know very well what

informed

voters in a working democracy would to do to them once they understood

just who

has depleted the national treasury to line their own pockets. No doubt,

he and

his political party will do anything to avoid the truth and will

propose

outwardly attractive solutions—like the health care bill that not only

expands

coverage but greatly benefits insurance companies and does little to

reduce

healthcare costs. They hope that these kinds of measures will lure the

majority

of voters who won’t bother to learn the details, but they will also

send a

clear signal to the moneyed classes that they won’t be inconvenienced

in the

least. As for those who continue to insist that there’s something fundamentally wrong with a democracy that doesn’t address the ever-growing income inequality the sheer madness of our open-ended military ventures in Afghanistan, the miseries of the sick and unemployed, the suffering of the near destitute and of the children and the old, they’ll be dismissed as being unrealistic in present circumstances and reminded that with the other party in power things would be even worse. The reason pessimists are multiplying is that we dishonor the intellect and the knowledge of history in this country by refusing to admit that corruption is the source of our ills. It takes no great mental effort to realize that there’s no effective political forces either in Washington or locally that are able to do anything serious to correct our self-delusions about being the world’s policeman, because any sensible solution would seriously cut into profits of this or that interest group. They say the

monkey scratches its fleas with the key that opens its cage. That may

strike

one as being very funny or very sad. Unfortunately, that’s where we are

now. March 10,

2011 11:45 a.m. Simic Interview

Ông nghĩ sao

về tình hình ở Yugoslavia? Chẳng có gì tốt để mà nói về cái đám dân chúng ở đó, chúng thù ghét nhau, và hở ra là làm thịt lẫn nhau. Và bây giờ thì có 1 cuộc nội chiến, và tôi nghĩ, bên nào thì cũng nhảm, và đều đáng đem ra đánh đòn. Tất cả cái đám CS đổi thành Dân Chủ, đổi thành Tân Quốc Gia Phát Xít, và tất cả đám còn lại. Tôi nghĩ những người dân Yugoslavia bị khùng bởi chính những kẻ ngày hôm qua, thời kỳ trước đây, [tức là trước ngày 30 Tháng Tư 1975 !] đã từng làm cho họ trở thành khùng, và khủng bố họ. Chẳng có thằng đéo nào dám vỗ ngực tự hào "tôi là người Yugoslavia" cả! Tôi chứng kiến quá nhiều điều quỉ ma, ngu ngốc và tất nhiên, có cái gọi là bi kịch ở xứ đó. Những con người có thiện tâm, và vô tội thì luôn luôn đau khổ, như họ vẫn từng đau khổ.

Tôi cũng mê

nhạc Trịnh Công Sơn, mê chết đi được. Theo tôi, những

người "mê chết đi được", nhạc TCS, phải là… VC! Gấu

có, chỉ một kỷ niệm với TCS, như đã kể ra trong bài viết, thật ngắn,

ngay khi

ông vừa nằm xuống. Subject:

Ve TCS Đành phải mạn phép bạn post cái mail lên đây, coi như của một độc giả nào đó. Vì Hai Lúa này cũng muốn viết thêm về TCS nhân "vụ án" PD, và những chấn động tiếp theo mới đây ở trong nước, và cũng nhận được vài cái mail về TCS. Thực

sự mà nói, quả có quá nhiều người theo đóm ăn tàn, viết về TCS, để được

hưởng tí

xái, nói theo 1 tay trong nước trên talawas đã có lần phạng Gấu, nhằm

nhắc khéo

tới những ngày GNV hầu hạ Cô Ba. Nhưng cái mail trên, của 1 độc giả TV,

quả là

1 gợi ý thật thú vị để mở ra 1 bài viết mới về TCS. Thường

thì người ta nói, trời cao, ở đây trời buồn, thành thử gió phải cao? Từ vườn

khuya bước về She walks in

beauty, like the night Baudelaire

writes, in "Recueillement":

"Entends, ma chère, entends, la

douce Nuit qui marche" Simic giải thích thơ của ông, “tái lập cái kỳ lạ cho cái rất ư bình thường, quen thuộc của kinh nghiệm”, "to restore strangeness to the most familiar aspects of experience." câu này có thể áp dụng cho lời nhạc TCS. * Nhân 10

năm ngày mất nhạc sĩ Trịnh Công Sơn sắp tới, nhóm có những hoạt động gì

để tưởng

nhớ một thành viên của nhóm? - Gia đình

nhạc sĩ Trịnh Công Sơn có làm nhiều chương trình rồi nên nhóm không làm

thêm gì

nữa. Bên gia đình nhạc sĩ Trịnh Công Sơn cũng không đặt vấn đề với anh

em nên

anh em chúng tôi không tham gia. Note: Đếch

chơi với tụi mi, được không? Kundera kể

chuyện, chủ tịch nước đứng trên bao lơn phủ dụ nhân dân. Trời lành

lạnh, ông

quên đem khăn, ông số hai bèn lấy khăn của mình choàng lên mình lãnh

tụ; khi

ông bị thủ tiêu, người ta bôi bỏ hình ông đứng kế bên chủ tịch nước,

nhưng cái

khăn thì vẫn còn đó! Đoạn trên,

GNV viết theo trí nhớ. Nguyên tác, sau đây, qua bản tiếng Anh, và là

đoạn mở ra

Cuốn Sách của Tiếng Cười và Sự Lãng Quên, The

Book of Laughter and Forgetting 1 In February

1948, the Communist leader Klement Gottwald stepped out on the balcony

of a

Baroque palace in Prague to harangue hundreds of thousands of citizens

massed

in Old Town Square. That was a great turning point in the history of

Bohemia. A

fateful moment of the kind that occurs only once or twice a millennium. 2 It is 1971,

and Mirek says: The struggle of man against power is the struggle of

memory

against forgetting Như vậy,

không phải cái khăn mà là cái nón! Cuộc chiến đấu của con người chống lại quyền lực là cuộc chiến đấu của trí nhớ chống lại sự lãng quên. Thú vị nữa,

là cái đoạn mở ra tác phẩm, thì lại được lập lại ở nửa phần sau. 1 In February

1948, the Communist leader Klement Gottwald stepped out on the balcony

of a

Baroque palace in Prague to harangue hundreds of thousands of citizens

massed

in Old Town Square. That was a great turning point in the history of

Bohemia.

It was snowing and cold, and Gottwald was bareheaded. Bursting with

solicitude,

Clementis took off his fur hat and set it on Gottwald's head. 2 If Franz

Kafka is the prophet of a world without memory, Gustav Husak is its

builder.

After T. G. Masaryk, who was called the Liberator President (every last

one of

his monuments has been destroyed), after Benes, Gottwald, Zapotocky,

Novotny,

and Svoboda, he is the seventh president of my country, and he is

called the

President of Forgetting. Trong cuốn

sách của ông, K cũng đã tưởng tượng ra được, trường hợp .. TCS bỏ nước

ra đi,

sau khi bị VC hành hạ, bị lũ bạn quí, cũ, thân… như HPNT, như TC, hay

Hồ Tôn Hiến

làm nhục: In 1972,

when Karel Klos, a Czech pop singer, left the country, Husak became

fearful. He

immediately wrote a personal letter to him in Frankfurt, from which,

inventing

not a word, I quotE; the following: Vào năm 19...82, TCS rời bỏ xứ Mít. Sáu Dân Hồ Tôn Hiến sợ quá. Ông liền lập tức viết thư riêng cho TCS: TCS thân mến, Hãy nghĩ đến

chuyện này: Sáu Dân Hồ Tôn Hiến vờ

cho đám

trí thức Ngụy vượt biên, đứa nào lỡ

bị địa

phương bắt thì ông đích thân lái xe hai bánh, đi trong đêm, tới hiện

trường ra

lệnh thả... Vậy mà ông VC học lớp 1 này không thể nào chịu nổi TCS rời bỏ xứ Mít! Bởi vì TCS đại diện cho âm nhạc không có hồi ức, thứ âm nhạc bên dưới nó, xương cốt của Beethoven, Ellington, tro than của Palestrina, Schoenberg được chôn vùi vĩnh viễn! Đâu có phải tự nhiên Trần Long Ẩn... lũ VC nằm vùng thứ thiệt, đếch thèm chơi với TCS. Và ngược lại! Chủ Tịt Lãng

Quên và Tên Ngu Si Âm Nhạc thì mắm xốt kít. Cả hai làm cùng một công

việc.

Đây là cái

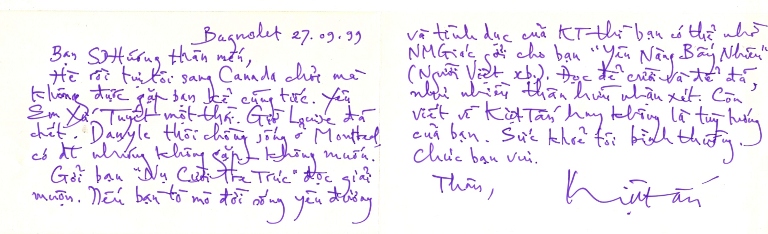

note của KT, kèm cuốn sách của anh. Sau đó, là chuyến đi Tây đầu tiên,

cũng thời

gian đó, bạn quí HPA đang ở Tây. Có 1 kỳ niệm thật tếu, là,

khi đến phi trường

chẳng làm sao nhận ra KT, thế rồi có một bà tiến tới gần, hỏi, có phải

Gấu

Đực & Gấu Cái đó không. Ui chao, đám Việt Minh,

khi về Hà Nội, thời kỳ đánh Tây, bị bắt, đúng là do cực khổ

quá mà ra.

Anh nào cũng ốm nhom, xanh lét, và nhất là, đều thèm phở. Thế là đám mật thám Tây chờ sẵn ở mấy tiệm phở, tóm thằng nào là y chang vừa ở rừng về! |