|

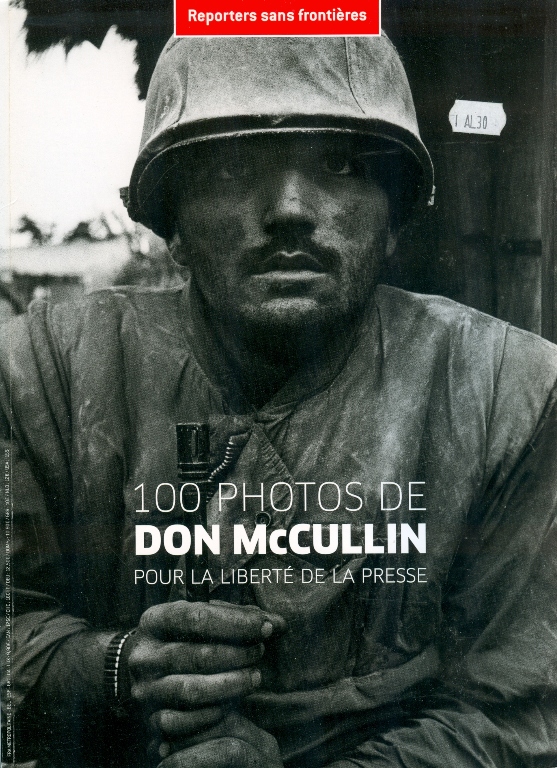

Shell-shocked

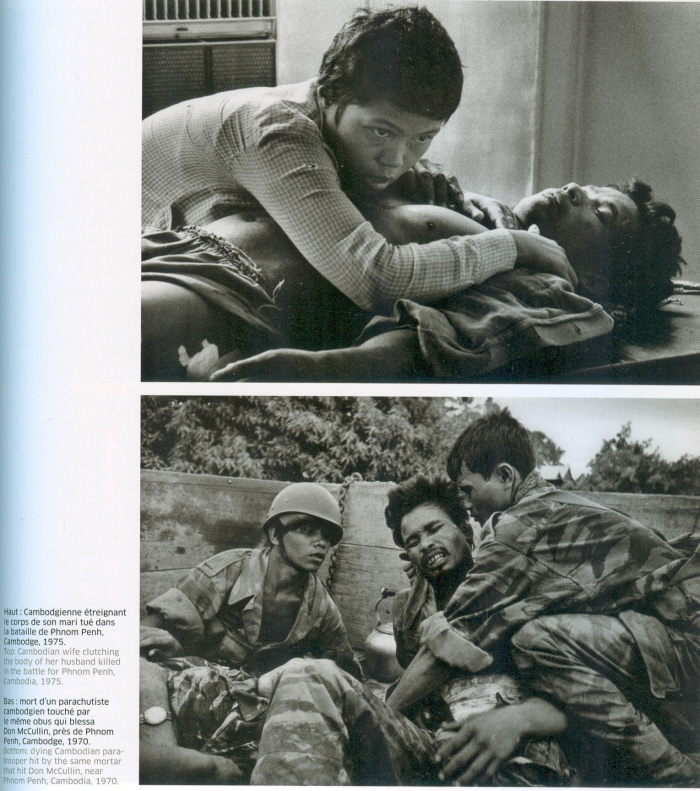

Photograph: Don McCullin

Don McCullin's most

celebrated image is his portrait of a

dazed American soldier, entitled Shellshocked

US Marine, Hue, Vietnam. It was

taken during the battle for the city of Hue in 1968 and, in its

stillness and

quiet intensity, says as much about the effects of war on the

individual psyche

as many of McCullin's more graphic depictions of conflict and carnage.

The eyes

that stare out beneath the grimy helmet are not staring at the camera

lens, but

beyond it, into nowhere. Hai con mắt thất thần, nhìn xuyên qua ống kính, tới hư vô! Bức hình trở thành “thương hiệu” của McCullin. Nhưng khi nhắc tới, ông nhăn mặt: Nó làm tôi đau đầu. Bởi vì nó xuất hiện ở khắp mọi nơi. Chẳng khác chi bức hình xử VC của Eddie Adams. " Et je suis las de cette

culpabilité, las de me

dire: Ce n'est pas moi qui ai tué cet homme, ce n'est pas moi qui ai

laissé cet

enfant mourir de faim. Je veux

maintenant photographier des paysages et des fleurs, je me condamne à

la paix. Don McCullin " J'aime la photographie,

je la respecte, je la vénère, je pense à elle tout le temps. Mais je

ne veux pas qu'on dise que je suis un photographe de guerre. Je suis un

photographe, tout simplement. Et c'est le seul titre que je revendique. Don McCullin J'admire depuis longtemps

le parcours héroique de Don

McCullin à travers les régions du monde les plus marquées par l'horreur

et la

souffrance de ces trente-cinq dernières années.(. .. ) Susan Sontag Ở Việt Nam,

McCullin sống giữa đám GI, và rất nhiều trong số họ nghĩ ông khùng. “Họ

năn nỉ thiếu điều giúi vô tay tôi khẩu súng, để bảo vệ và rất ư kinh

ngạc,

khi thấy tôi lắc đầu. Một khẩu súng thì làm gì có chỗ trong bộ đồ nghề

của một

nhiếp ảnh viên. Bạn có đó, như một quan sát viên khách quan." Sawada là bạn thân của Gấu! Thực sự là vậy. Gấu đã viết về anh trong bài viết Tên của cuộc chiến, nhưng, bữa nay bèn nhớ ra, anh là người độc nhất tặng quà cưới, rất bực khi thấy Gấu không mời dự, và khi biết đám cưới tại Cai Lậy, đầy VC ở đó, thì bèn cười, và dẫn Gấu qua terrace ở mãi tít trên thượng lầu khách sạn Majestic làm 1 chầu ăn sáng. Một nhiếp ảnh

viên của UPI, Gấu quên mất tên, bị VC giết, vì đưa

cái máy hình hướng

về phía họ, và họ nghĩ, đó là khẩu súng. Trong chiến tranh, làm một

quan

sát viên

khách quan cũng khó lắm. Trong cuộc chiến Việt Nam, hình

xử VC của Loan đâu có khủng bằng hình VC

làm thịt cả 1 loạt ký giả, nhiếp ảnh viên, ngồi xe Jeep lùn, có gắn tấm

bảng

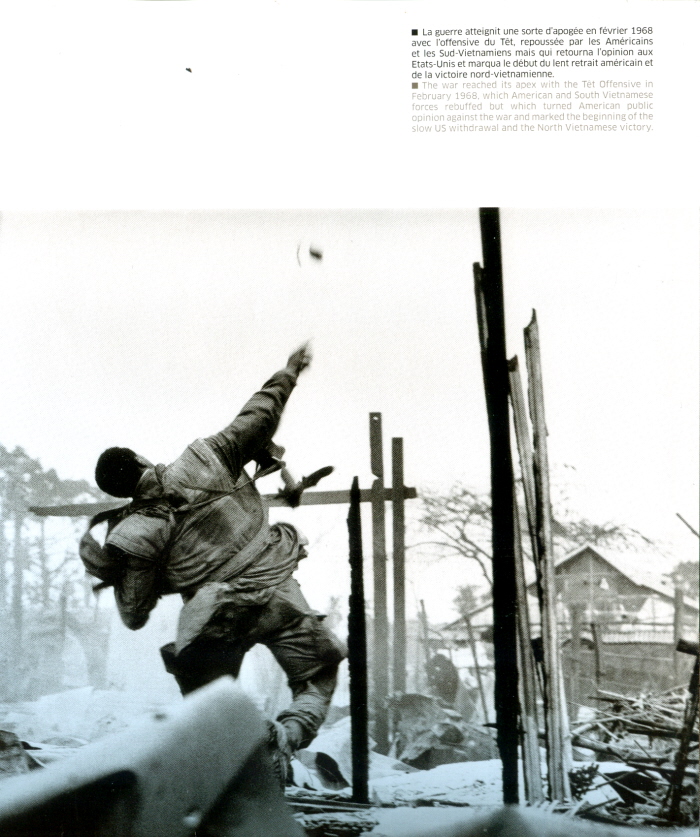

Press, trong trận Mậu Thân? Huế Mậu Thân  GI quăng lựu

đạn, liền sau đó, trúng đạn VC.

Marine américain lancait une grenade quelques secondes avant d'être blessé à la main gauche par un tir, offensive Hué, sud Viet-nam, 1968  Nhìn lại cuộc chiến Việt Nam Với gương mặt

khắc khổ, giọng nói từ tốn, ông McCullin kể lại cảm xúc và những nỗi

bất an của

mình qua một số bức ảnh tiêu biểu ông đã chụp tại cuộc chiến Việt Nam

từ năm

1965 đến 1973 khi còn là phóng viên ảnh chiến trường cho tờ The

Illustrated

London News. BBC Còm của Gấu

Cà Chớn: Kinh nghiệm

riêng của GCC:  Don McCullin

parle du moment fugitif où s'établit

le rapport avec son sujet, l'instant du "oui". Ce

moment d'intimité nue, lorsque lui ou elle le voit et lui pardonne, au

seuil de

la mort, de la famine, d'un chagrin inconsolable, quand leur enfant git

mort

sur le sol de l'entrée, tué par une bombe lors de l'attaque : quand

même

"oui. McCullin is

talking about the elusive moment of connection with his subject - the

"yes", the moment of naked affinity where he or she sees him, and

forgives him, at death's edge, starving, inconsolably bereaved, when

their own

child lies dead on the hall floor, bombed in the attack: still "yes.

Yes,

take me. Yes, take us. John Le Carré dans la

préface de Au coeur des ténèbres, Robert Laffont,

Paris, 1980. (1) Cái từ

"ma", “my” trong "ma souffrance", "my pain", quá

thần sầu. Câu tưởng đơn giản, mà kinh khủng quá. Theo từ điển

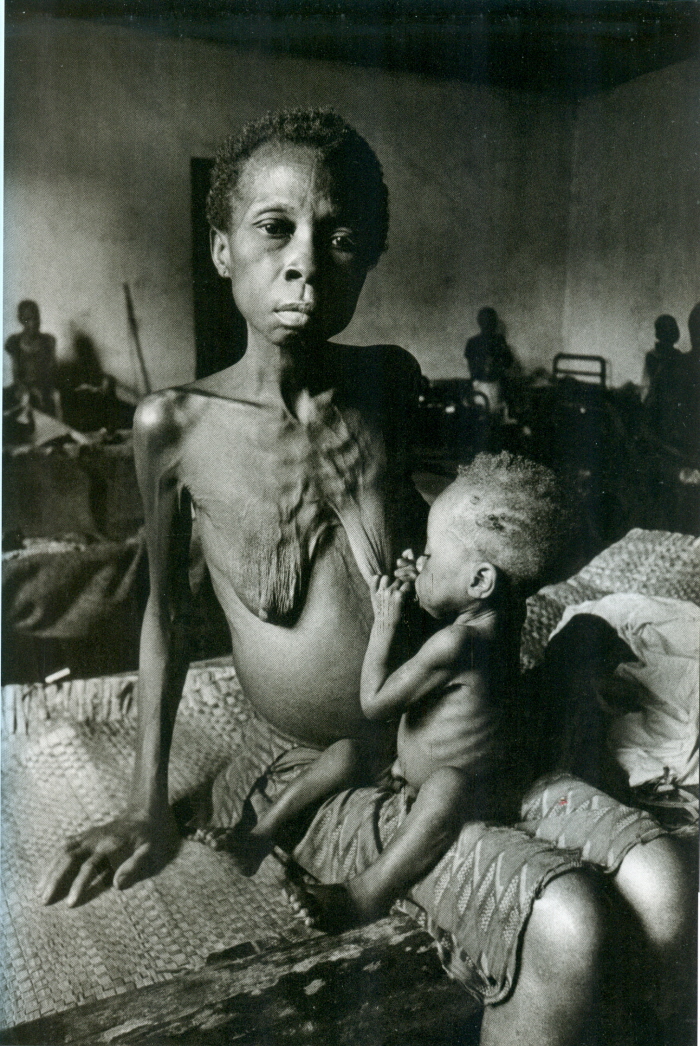

trên mạng : Bà mẹ 24 tuổi

và đứa con, Biafra, Nigeria, 1969 DON

McCULLIN'S IMPOSSIBLE PEACE Between

photographing the construction of the Berlin Wall in the summer of 1961

and his

work on the ravages of AIDS in southern Africa in 2001, Don McCullin

has never

ceased observing the suffering of others through the major conflicts of

four

decades. It is a look filled with anger, sadness, and even despair at

the

unspeakable cruelty man inflicts on his fellow creatures. A gaze

charged with

disbelief, compassion, and solidarity with the weakest, the destitute,

the

outcast, and victims of unacceptable circumstance.  Shaped by War: Photographs by Don McCullin Shell-shocked

Photograph:

Don McCullinDon

McCullin's most celebrated image is his portrait of a dazed American

soldier,

entitled Shellshocked US Marine, Hue, Vietnam. It was taken during the

battle

for the city of Hue in 1968 and, in its stillness and quiet intensity,

says as

much about the effects of war on the individual psyche as many of

McCullin's

more graphic depictions of conflict and carnage. The eyes that stare

out

beneath the grimy helmet are not staring at the camera lens, but beyond

it,

into nowhere. Surprisingly,

when I ask McCullin about the

photograph, which features in this retrospective of his reportage in

Manchester, he grimaces. "It kind of gets on my nerves now," he says,

"because it has appeared everywhere. It's like the Eddie Adams shot of

the

execution of a Vietnamese prisoner." Now 64, and

married for the third time, McCullin lives and works in rural Somerset.

These

days, he concentrates on landscape photography and has just completed

what he

says will be his last book, the epic Southern Frontiers: A Journey

Across the

Roman Empire. "It brings me a kind of peace," he says, "until I

hear the local hunters shooting. Gunfire is a prelude to war for me. I

feel I'm

back there on some godforsaken road passing dying soldiers lying in

culverts." There is a

sense when talking to McCullin that he carries a great burden of loss

and

regret. He has, he says, seen too much in his lifetime and it has left

its mark

on him. He is recognised as our greatest living war photographer,

though he

bridles at the term. "Whatever I do, I have this name as a war

photographer," he says, ruefully. "I reject the term. It's reductive.

I can't be written off just as a war photographer." This

extraordinary exhibition will do nothing to help his cause. Alongside

his

photographs of conflicts in Cyprus, the Belgian Congo, Vietnam,

Cambodia,

Lebanon and beyond, many of which have not been seen before, it

features

contact sheets and magazine spreads from his halcyon days at the Sunday

Times

magazine in the early 1970s. There is also a wealth of personal

material: his

passports, his army boots and helmet as well as his many cameras, one

of which,

a beloved Nikon F, was fractured by a sniper's bullet in a rice field

Cambodia

in 1970 just as he held it up to his face. In Vietnam,

McCullin lived among the American soldiers, many of whom, he says,

thought him

mad. "They kept offering me guns for my protection and, to their utter

astonishment, I kept refusing. A gun has no place in a ¬photographer's

kit. You

are there as an objective observer." He tells me that many of his

contemporaries did carry guns, though. "Dana Stone and Sean Flynn [son

of

the Hollywood actor, Errol Flynn] were straight out of Easy Rider,

riding

around on motorcycles carrying pearl-handled pistols. Cowboys, really.

I think

they did more harm than good to our profession." Both Stone

and Flynn, along with McCullin's friend Gilles Caron, were killed in

Cambodia

in 1970/71, having been captured by the Khmer Rouge. "They were held in

a

jungle clearing and then put to death in the most appalling way," he

says

quietly. Another friend, the great Japanese photographer Kyoichi

Sawada, was

also captured there but somehow talked his way free. He, too, was

killed later.

I ask McCullin if he feels like one of the lucky ones. "I guess so. I

signed up for a job where you have no guarantees. Why should you? War

is war,

war means death. If you go and come back, you are lucky." It was

Sawada who photographed McCullin as he lay wounded in a field hospital

in Phnom

Penh in 1970, having been hit by fragments of a mortar shell. McCullin

says he

was most afraid, though, when he was captured by Idi Amin's soldiers in

Uganda

and held prisoner for four days. "They dug pits outside our cell. The

sense that something awful was going to happen was constant and almost

overwhelming." Closer to

home, McCullin created some of the most memorable images of the early

Troubles.

During a riot in Derry, he was blinded by CS gas and recovered in a

dingy house

that reminded him of his working-class upbringing in Finsbury Park in

north

London. "I was caught between the two sides, with the Provos warning me

off one day and the British army chasing me the next." His images from

there are often surreal: a well-dressed young man nonchalantly carrying

a wrapped

parcel past a soldier who is taking aim at rioters; a woman taken aback

in her

hallway as soldiers in riot gear rush down her street like samurai.

"Oh,

that was just a gratuitous piece of luck on my part," he says, smiling.

"That woman in the doorway, she makes the picture, really." I ask him

if, even in the chaos of conflict, he thought about formal composition.

"Always. Somewhere in your head, you think about how the image will

appear

later. You have to. You want people to see it and be impressed." He

singles out his great photograph of an American soldier hurling a

grenade.

"I was as much a target for the snipers as he was, but I got the shot

that

I saw in my head." McCullin

famously prints his own photographs. Has he ever developed a print and

been

shocked by the result. "The albino boy," he says, without hesitation,

referring to his heartbreaking image of a starving Biafran child

clutching an

empty corned beef tin. "The day I came across that boy was a killer day

for me. There were 800 dying children in that schoolhouse. The boy is

near

death. He is trying to support himself. And to see this kind of

pathetic

photographer appear with a Nikon around his neck …" He falls

silent again for a moment. "Some times it felt like I was carrying

pieces

of human flesh back home with me, not negatives. It's as if you are

carrying

the suffering of the people you have photographed." At the

Imperial War Museum, McCullin's vivid and sometimes shocking testimony

is war

reportage as it used to be. He would not, he says, want to be a young

war

photographer in Iraq or Afghanistan. "No way. I mean, the idea of

agreeing

to be embedded? No. It's an absolute tragedy. We spent years

photographing

dying soldiers in Vietnam and they are not going to have that anymore.

I

understand that, but you have to bear witness. You cannot just look

away." |