Album

|

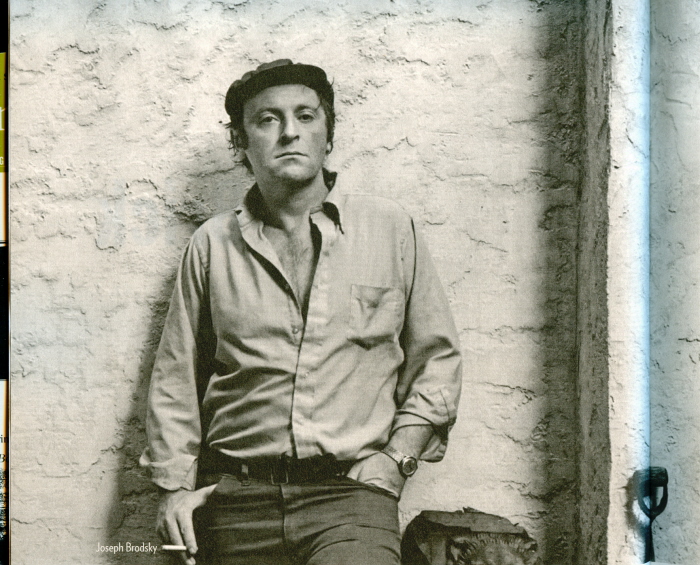

Joseph

Brodsky @ Toronto Oct 1995 Số ML đặc biệt

về Kundera, bài hay nhất theo Gấu, là

bài viết về thơ. Nói ra thì bảo là Gấu

phách

lối, nhưng Gấu phát giác ra điều này rồi, ngay khi đọc Những Di Chúc Phản

Bội, vá áp dụng ngay vào đấng Văn Cao, một mình đóng hai vai,

vừa thi sĩ vừa đao phủ. Chúng

ta có định nghĩa về thơ tự do của Brodsky, chúng ta có định nghĩa về

thơ tự

do của…

GNV [bạo động trong thơ TTT]. Ðâu chỉ là

thời của ghê rợn, cái thời mà VC ngự trị nước Mít. Nó còn là thời của

vãi linh

hồn, của đường ra trận mùa này đẹp lắm, mặt trời chân lý chói qua tim. Bài viết hay

nhất về Kundera, theo Gấu, là bài trên tờ Books, báo Tây, mà tên báo bằng

tiếng

Anh. Trên TV đã giới thiệu.

Bài viết về

Kundera trên tờ Books, số mới nhất,

Tháng Ba 2011, [tờ này theo Gấu, bảnh nhất hiện giờ, vượt biên cương

Pháp, vì

giới thiệu không chỉ văn Tây, không như

tờ Magazine Littéraire, thí

dụ], thật tuyệt. Bài viết,

nhân Kundera vô Pléiade, ngay từ khi còn sống, nhân ở quê hương của ông

cho xb

một tác phẩm tập thể, [ouvrage collectif], về ông, nhưng hơn hẳn thế,

đưa ra 1

cái nhìn thật là bảnh về Âu Châu! Ông ta hết

còn là 1 tác giả của 1 cái xứ ở dưới đó, một xứ CS! Trung Âu là

1 ám dụ về phía âm u, une allégorie du côté sombre, của thế kỷ 20,

thông qua,

via, sự vinh danh của cái “căn cước thật” của nó. Tiểu thuyết,

một biểu hiện sáng suốt, une expression lucide, của thế giới. Nếu tiểu

thuyết là 1 nghệ thuật, thì sự khám phá ra văn xuôi, la prose, là nhiệm

vụ của

nó, và không có 1 thứ nghệ thuật nào khác làm được điều này.

Cuộc phỏng vấn

được thực hiện tại Ngày Hội Quốc Tế Những Tác Giả, được tổ chức tại

thành phố

Toronto, tháng 10, 1995. Joseph Brodsky và tôi gặp nhau trong phòng

thay đổi

quần áo, nhỏ, xập xệ, ở ngay phía bên phải

sàn trình diễn. Brodsky xem ra có vẻ cũng bứt rứt như là tôi, hút thuốc

lá liên tục hầu như trọn 90 phút của cuộc trao đổi. Mr. Brodsky, ông làm thơ

bằng tiếng Anh, và bằng

tiếng Nga. Ông không phải là người độc nhất viết bằng hai ngôn ngữ,

nhưng hiếm

có một nhà thơ lớn làm điều này. Ngoài ông ra, thì tôi nghĩ tới Rilke

và

Celan. Ông có khi nào lâm vào phút khủng

hoảng, khi ngồi xuống bàn viết, và đụng ‘vấn nạn’, nào làm thơ, nhưng

bằng tiếng

Anh, hay là tiếng Nga? JB: Không.

Không, chuyện xẩy ra không phải như thế. Tôi không thường xuyên làm

thơ bằng tiếng Anh. Giản dị mà nói, thì nó giống như 1 thứ sides-show,

trình diễn

phụ, và bởi vì sideshow, tự nó có một lời giải thích cho câu hỏi của

ông. Tôi lâu

lâu làm thơ bằng tiếng Anh, vì thực sự muốn làm 1 điều thật khác đi. Và

điều

thường xẩy ra, thì đó là, ước muốn cưỡng lại, cố kiềm chế mình,

cố làm sao đừng để nó cám dỗ, đừng tự buông xuôi, có thể nói như vậy.

Người Nga

sẽ nói, "Ðừng buông xuôi, bỏ chạy văn hóa

của riêng bạn, đừng đi quá, đừng vượt qua". Nhưng những cám rỗ, chúng

láu cá, xảo quyệt lắm, nếu bạn cưỡng lại chúng quá lâu, thể nào

cũng đưa đến tình trạng tẩu hỏa

nhập ma, thành thử tốt nhất, lâu lâu chơi 1 đường làm thơ bằng tiếng

Anh, tôi

chọn kiểu chơi này. Nhưng thỉnh thoảng, tôi giản dị

bảo mình, phải viết ra, làm ra một nhịp điệu. Cơ bản, về

lâu về dài, sở trường hay sở đoản mà nói, tôi là 1 nhà thơ truyền

thống, làm thơ theo

vần điệu, và chính cái gọi là nhịp điệu đề xuất mgôn ngữ thơ. Hoặc nhịp

Anh, hoặc

nhịp Nga. Chuyện gì xẩy

ra khi ông dịch? Chuyện gì xẩy ra cho những nhịp điệu, khi đó? Tôi muốn

nói, cái

đầu tiên mất tiêu khi dịch, là nhịp điệu ở nguyên tác. Quả thế, quả thế, thưa bạn. Ðiều này cực làm phiền tôi, cơ bản mà nói. Sau cùng, thì nó đếch làm phiền tôi, ấy, phải nói, làm phiền tí tí [cười]. Có một mức độ trí thức, về nhịp, ở nguyên tác, và có một, ở chuyển dịch, và hai mức độ đó thì như nhau, và đó là điều bạn đang nhắm tới. Trên tất cả, nếu tôi có gì tự hào về mình, trong bất cứ gì gì, thì đó là về phẩm chất nhịp điệu thơ tôi. Nếu tôi có bất cứ tham vọng, thì đúng là về cái chuyện được đời xưng tụng như là một nhà thơ nhịp điệu bảnh, ra trò [cười]! Với nền tảng

của ông, như nhà thơ truyền thống, cổ điển, một tham vọng như thế đâu

có... ‘mỏng’? Câu hỏi chính

với thơ tự do – không phải tôi, mà là Eliot phán – câu hỏi chính với

thơ tự do là, Tự

do từ cái gì? Tất cả vấn đề là, thơ tự do bật ra như là một công

trình kỷ niệm

của một cú lên đường cá nhân, của một cơn khủng hoảng cá nhân, của một

cá nhân

lớn này, hay nọ. Trong tiếng Anh, đó là Eliot. Từ quyết định, sắc thái

quyết định,

là ‘phát triển’. Và bạn không thể có sự phát triển nếu không có sự thay

đổi lớn

lao nào đó. Và những ai làm thơ tự do thì giản dị phải, theo một nghĩa,

lập lại

cũng vẫn sự phát triển. Nói một cách khác, họ có được cũng vẫn kết quả

thực, họ

lập lại những gì họ đọc, những gì họ thừa hưởng. Hãy nhớ lời cảnh cáo

của

Goethe, bạn phải hưởng cái bạn thừa hưởng. Nghe thật nản, bởi vì bạn

chẳng thể có

cảm quan nào về tự do, nếu không dám làm việc vì nó. Note: Brodsky là nhà thơ cổ

điển, truyền thống, trọng niêm luật, nhịp điệu, thành thử

ông quá nặng lời với thơ tự do. Tuy nhiên,

nhận xét về thơ tự do như là cú khởi đầu, cú khủng hoảng, cú đặc dị của

một thế

giá lớn, mà với Brodsky, là trường hợp Eliot, thì với… GNV, là trường

hợp thơ tự

do của TTT. Khủng thật. Gấu đã nhận ra điều này,

khi viết về thơ TTT, ngay từ

những năm 1973, cái "gì gì", tính bạo động

trong thơ tự do của TTT: Những người

yêu thơ Thanh Tâm Tuyền, yêu chất "bạo động của bạo động", nam

tính... của thơ ông, khởi từ những dòng thơ cách mạng trong Tôi không còn cô độc,

tới Liên, Đêm... có thể sẽ

không thích những dòng thơ "hiền từ" của Thơ ở đâu xa. Tôi

vẫn nghĩ ông bắt đầu bằng thơ tự do, ngược hẳn lời khuyên của

Borges, (1) chính vì chất hung bạo "đặc biệt" của thơ ông: Thơ không

thể èo uột, yếu đuối, bệnh hoạn, không phải là nơi trốn chạy, ẩn náu...

Nó là mắt

bão: trung tâm của mọi bạo động. Ông chỉ trở lại với thơ vần, sau trại

tù. Với

tôi, Thơ ở đâu xa mới là cực

điểm của bạo động trong thơ: thiền. Trích

tiên bị

đầy (vào trại tù), trở về trần. (1) Source SAM SOLECKI This

interview took place at the International Festival of Authors in

Toronto in

October 1995. Joseph Brodsky and I met in a small, shabby dressing room

just to

the right of the stage. Brodsky seemed almost as nervous as I was and

chain-smoked

through the entire ninety minutes that we were together. My first

impression

was of a man whose health might be precarious and who spent far too

much time

at his desk, like W. H. Auden, his idol. I broke the ice by telling him

that I

had previously interviewed Czeslaw Milosz for the CBC a couple of days

after he

won the Nobel and that Brodsky would be my second and probably last

winner of

the prize. He asked me whether Milosz, whom he knew very well, had

smiled

during our time together. I told him he hadn't during the interview,

but I

remembered a guarded smile during a dinner we had in 1989 after the

fall of the

evil empire. I followed up by reassuring him that I wouldn't be asking

him any

personal questions. The focus would be on his writing, his career, and

poetry

in Russian and English. We talked for a few minutes about Akhmatova and

Mandelstam, and I had just finished giving him the lead-off question

when the

emcee came in. He began by telling us the latest news about Princess

Diana's

love life and asking, "Is there anyone who hasn't slept with her?" I

immediately put up my hand. Brodsky's response was more interesting and

volatile. The blood had rushed to his face and he barked out in his

Russian-scented English, "Never forget, sir, that she is royalty and

you

aren't." It occurred to me that perhaps I should save the situation,

but

my mind seized up and all I could think of saying was something like,

"How

about those Leafs?" Fortunately one of the stagehands came by at that

moment to tell us that there were about five hundred people in the

packed room,

the cameras were ready, and it was showtime. I didn't get a chance to

tell

Brodsky my favorite Nobel Prize joke. ... Ông ta [the

emcee] bắt đầu nói về những tin tức mới nhất về cuộc đời tình ái của

Princees Diana,

và hỏi: “ Có ai chưa ngủ với công nương?"

JB:.... Among the

foreigners, those who I wanted to read in translation, well, you've

got Milosz already. I would add two more Polish poets. One is Zbigniew

Herbert,

and another is Wislawa Szymborska, a wonderful lady. ss: Both

write in free verse. JB: Both of

them do. But they've earned the right to do so, and I'll tell you why.

It's not

exactly my argument; it's Milosz's own argument. In his Norton

Lectures, I

think, he puts forth the following idea to explain why Polish poetry is

abandoning

traditional metres. It's because, he says, in Poland the traditional

verse has

been identified with the culture and world order that brought the

country to

catastrophe. So, in a sense, traditional verse is the verse of the old

guys,

the past. ss: I asked

Czeslaw Milosz about a week after he won the Nobel Prize whether he

ever

worried about losing his command of Polish because of his long exile.

Has this

ever troubled you? JB: Yes, I worried about that. Especially initially, I did. Now I don't, perhaps to my own detriment, but I don't. I'm simply of the mind that we're all being brought up to believe that it's the diction of the street, of the people, that literature should abide by. I'm of the opinion that it's the other way around. It's the street that should abide by the language of literature. Dante is an illustrious example. I think Italians today speak, or at least are capable of speaking, not the discourse of the street or television but of their literature. When I feel anxious about all this I think about somebody like the great Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, who wrote in a language that wasn't Greek. It wasn't demotic or what the Greeks calls katharevousa. At best it was the idiom of the Greek colony in Alexandria, in Egypt. And yet it resulted in great poetry. Trong

số những ngoại nhân, những người mà tôi muốn đọc họ qua bản dịch, bạn

biết có Milosz.

Tôi muốn thêm vô hai nhà thơ Ba Lan. Một là Zbigniew Herbert, và người

kia là Wislawa

Szymborska, một phu nhân tuyệt vời ss:

Cả hai đều làm thơ tự do. Quả

thế. Nhưng họ có quyền làm thơ tự do, và tôi sẽ nói tại sao. Không phải

tôi, mà

là Milosz, trong những bài đọc tại Norton, theo tôi. Ông cho rằng, thơ

Ba Lan bỏ

truyền thống thơ vần là vì ở Ba Lan, thơ

truyền thống thì bị đồng nhất với văn hóa và trật tự thế giới, ba thứ

quỉ quái đã đưa xứ sở này tới

thảm họa. Như vậy, theo một nghĩa nào đó, thơ truyền thống là thơ của

đám già,

của quá khứ. ss:

Tôi có hỏi Czeslaw Milosz, tuần lễ sau khi ông được Nobel liệu ông có

ớn cái

chuyện quên mẹ tiếng Ba Lan vì lưu vong quá lâu. Ông có từng bị khốn

đốn với

chuyện này không? JB: Làm sao không. Nhất là lúc thoạt kỳ thuỷ. Nhưng giờ thì hết rồi. Ðây là do đầu óc ngu ngốc mà ra. Bởi vì chúng ta thường đinh ninh một điều là đường phố, con người, quê hương “mỗi người chỉ có một”… mấy thứ đó nuôi dưỡng chúng ta, nếu không có chúng, là chúng ta đếch lớn nổi thành người! [Ðúng thế, tôi

cũng lo cái chuyện đó, nhất là thoạt kỳ thuỷ, tôi có lo. Bây giờ thì

hết rồi, và có

thể đây là sự tổn hại của riêng tôi, nhưng quả là không. Nói một cách

giản dị,

có thể chúng ta được sinh ra đời, rồi trưởng thành cùng với đời, là để

tin rằng

đường phố, người ngợm và tiếng nói của họ đưa ra lời phán bảo, và văn

chương sống

được, có được là nhờ nó. Tôi thì lại tin ngược lại: Chính đường phố

phải

nhớ ơn… thơ của tôi, thí dụ vậy! Nói khiêm tốn thì là như thế này,

đường phố tuân

thủ văn chương. Dante là trường hợp chứng minh hiển hách điều này. Tôi

nghĩ

người Ý bây giờ nói, hay ít nhất, có thể nói, không phải diễn từ của

đường phố,

hay của TV, nhưng mà là văn chương của họ. Khi tôi cảm thấy âu lo vì

tất

cả điều này, thì tôi lại nhớ đến một người nào đó như là nhà thơ Hy

Lạp, Constantine

Cavafy, viết trong một ngôn ngữ không phải tiếng Hy Lạp. Thứ tiếng này

không thông

dụng, không phải thứ tiếng “katharevousa” mà người Hy Lạp gọi. Tốt

nhất, thì phải

gọi nó là một thứ thành ngữ của vùng Greek colony ở Alexandria, ở Ai

Cập. Nhưng nó đem

tới một thi ca lớn.] Thi sĩ TTT, cũng

có lần đưa ra nhận xét, người đời coi thi sĩ là những tên mơ mộng,

không tưởng,

không thực, nhưng đúng ra phải nói ngược lại. Thi sĩ nói ra những giấc

mộng lớn,

mà con người chưa đủ khả năng, “bất tài”, không làm sao thực hiện.

Bởi vì ông

nhắc tới những nhà thơ lớn lao, tôi nghĩ có lẽ chúng ta xoay câu chuyện

quanh đề

tài này, và nhắc tới 1 nhà thơ vĩ đại nhất của thế kỷ. Wystan Hugh Auden Ông nhắc tới, trong bài “Ðể làm hài lòng một cái bóng”, “To Please a Shadow”, một trong những lý do ông học tiếng Anh, hay trở nên ngày càng quấn quít với nó, là để “thấy mình gần gụi với một người mà tôi nghĩ là một đầu óc vĩ đại nhất của thế kỷ 20, Wystan Hugh Auden". Và rồi ông bàn về những phẩm chất của ông ta. Những phẩm chất mà tôi đặc biệt thích thú của ông ta, là ‘equipoise’ và ‘wisdom’. Vai trò của Auden trong sự nghiệp của ông như là 1 thi sĩ, là gì? Tôi sẽ trả lời

câu hỏi này như tôi có thể. Ông ta đi vô tôi, enter, theo 1 nghĩa nào

đó, ông

ta đi vô cuộc đời của tôi. Thì cứ nói như vầy, chúng ta đang nói

chuyện, ở đây,

tôi đang ngồi đây, và tôi cảm thấy ông ta là một phần của tôi… Khi tôi

gặp ông ta

22 năm trước đây, tôi 32 tuổi, và ông ta chỉ còn sống được 1 năm nữa… Cũng trong cùng

bài essay, ông nó về sự quan trọng đối với mọi độc giả là có ít nhất 1

nhà thơ để

mà lận lưng. Với ông, hẳn là Auden. Nhưng

ngoài Auden ra, liệu Eugenio Montale có xứng đáng… Xứng đáng quá

đi chứ. Tôi nghĩ phải thêm vô Thomas Hardy, Robert Frost… Tôi thấy mình

gần Frost

hơn so với Auden. Bạn có nhớ không Lionel Trilling đã từng gọi Frost là

1 nhà

thơ khủng khiếp. Còn Eliot.... Bishop, bà này Canada chính gốc. Trong

số ngoại nhân,

làm sao bỏ qua Milosz. Wislawa Szymborska mà không bảnh sao, a

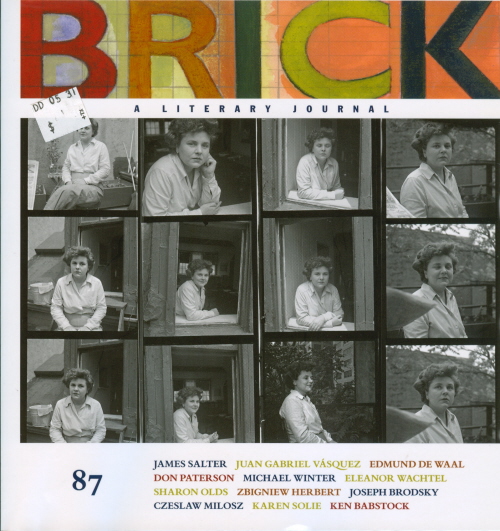

wonderful lady…  Số Brick,

Nhật ký văn học, đặc sản Toronto,

cây nhà lá vườn, tình cờ Gấu cầm nó lên ở tiệm sách, và ngỡ ngàng khám

phá ra cả

1 lô bài viết thật là tuyệt vời, đa số về thơ. Chưa kể bài viết về Trăm Năm Cô Ðơn của Garcia Marquez, của

1 tay đồng hương với tác giả, phải nói cực ác, và vấn nạn mà nó nêu ra:

Làm sao

những xứ sở Mỹ Châu La Tinh tiếp tục viết, dưới cái bóng khổng lồ, ma

quỷ của Trăm Năm Cô Ðơn? [Ui chao, Gấu

lại nhớ đến Nỗi Buồn Chiến Tranh của

Bảo Ninh: Có vẻ cái vía của nó khủng quá, khiến đám nhà văn VC, kể cả

Bảo Ninh,

như bị teo chim, hết còn viết được nữa!] Bài phỏng vấn

Brodsky cũng quá tuyệt, trong có 1 nhận xét của ông về thơ tự do, thần

sầu. Cuộc

phỏng vấn xẩy ra 1 năm sau khi Gấu tới định cư Toronto, Canada, cũng là

1 chi

tiết thú vị. Hai bài về nhà thơ Vat cũng thần sầu, 1 ông kể kinh nghiệm

lần đầu

làm thơ, khi còn là 1 đứa con nít, và cũng là 1 lần tiên khám phá ra 1

cái nơi

mà người ta gọi là nhà tù. Về già, ông vưỡn cứ làm thơ, bất chấp người

ta nói:

Già như mi cớ sao làm thơ? Gấu về già mới

có được cái thú làm thơ, dịch thơ, thành thử rất tâm đắc với câu trên: “He’s so old, isn’t he ashamed to write poems?”   SAM SOLECKI This

interview took place at the International Festival of Authors in

Toronto in

October 1995. Joseph Brodsky and I met in a small, shabby dressing room

just to

the right of the stage. Brodsky seemed almost as nervous as I was and

chain-smoked

through the entire ninety minutes that we were together. My first

impression

was of a man whose health might be precarious and who spent far too

much time

at his desk, like W. H. Auden, his idol. I broke the ice by telling him

that I

had previously interviewed Czeslaw Milosz for the CBC a couple of days

after he

won the Nobel and that Brodsky would be my second and probably last

winner of

the prize. He asked me whether Milosz, whom he knew very well, had

smiled

during our time together. I told him he hadn't during the interview,

but I

remembered a guarded smile during a dinner we had in 1989 after the

fall of the

evil empire. I followed up by reassuring him that I wouldn't be asking

him any

personal questions. The focus would be on his writing, his career, and

poetry

in Russian and English. We talked for a few minutes about Akhmatova and

Mandelstam, and I had just finished giving him the lead-off question

when the

emcee came in. He began by telling us the latest news about Princess

Diana's

love life and asking, "Is there anyone who hasn't slept with her?" I

immediately put up my hand. Brodsky's response was more interesting and

volatile. The blood had rushed to his face and he barked out in his

Russian-scented English, "Never forget, sir, that she is royalty and

you

aren't." It occurred to me that perhaps I should save the situation,

but

my mind seized up and all I could think of saying was something like,

"How

about those Leafs?" Fortunately one of the stagehands came by at that

moment to tell us that there were about five hundred people in the

packed room,

the cameras were ready, and it was showtime. I didn't get a chance to

tell

Brodsky my favorite Nobel Prize joke. ... Ông ta [the

emcee] bắt đầu nói về những tin tức mới nhất về cuộc đời tình ái của

Princees Diana,

và hỏi: “ Có ai chưa ngủ với công nương?" ss: One of the pleasures of introducing a Nobel Prize winner is that you can actually say, "This person needs no introduction" and mean it. But just in case there's one person here this afternoon who thinks we're meeting Czeslaw Milosz or another Nobel Prize winner, here's a brief introduction to Joseph Brodsky. He was born in Leningrad in 1940 and established his reputation as a poet in the decade prior to being compelled to leave the Soviet Union in 1972. He has lived in the United States for the past quarter-century, and he became a citizen in 1977. His first book in English appeared in 1973, translated by George Kline. A selected poems, it was a remarkable breakthrough, with a foreword by W. H. Auden. This was followed by A Part of Speech in 1980 and To Urania in 1988. He has also published Less Than One, a collection of essays, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award. It's going to be followed, in a few months, by another collection of essays, even though he has in the past spoken rather disparagingly of prose. [This collection was published in 1995 as On Grief and Reason.] His most recent book is Watermark, a meditation on Venice. [A third collection of poetry in English, So Forth, was in press upon his death in 1996, and all his English poems and self-translations were collected in Collected Poems in English in 2000.] Even before he received the Nobel Prize in 1987, there was a consensus among Russian and English-speaking critics that he is the major poet of the post-Akhmatova generation. I assume this canonical judgment probably leaves Mr. Brodsky looking nervously over his shoulder, worrying whether he's accompanied by Euterpe, one of the muses of poetry, or Nemesis. I'm very

happy to welcome Joseph Brodsky to Harbourfront, and I will begin by

asking him

about what might be called a linguistic ambiguity in his career. Mr. Brodsky,

you have written poems both in English and in Russian. You're not

unique in writing

in two languages, but it's relatively rare for a major poet to do so.

Offhand,

I can think of Rilke and Celan. Do you ever have a moment of crisis

when you

sit down to write a poem and find yourself wondering which language to

choose? JB: No. No,

it doesn't happen that way. Well, to begin with, I don't write poems in

English

that often. I just simply, how should I put it? I do it as a sort of

sideshow;

and precisely because it is a sideshow, it has in itself an answer to

your

question. I do it simply because, now and then, I have almost a desire

to do

something different. But it's usually best to resist that desire and

control

myself, not to yield to that temptation, not to abandon myself, so to

speak.

The Russians would say, Don't abandon your own culture, don't cross

over. But temptations

are a tricky thing. If you do resist them for too long, that leads to

neurosis;

so my policy, if there is any, is to deal with them from time to time.

Well,

that's one thing. But sometimes I simply have to write a rhyme. I'm

basically,

by and large, a traditional poet who writes in rhymes, and it's the

rhyme that

suggests the language of a poem. And it's either an English rhyme or a

Russian

rhyme. That's the way it starts. ss: What

happens when you translate? What happens to the rhymes? I mean, the

first thing

lost in translation is the original soundscape. JB: Indeed.

Yes, well, that doesn't bother me very much, basically. Actually, it's

not that

it doesn't bother me, it bothers me a little. [laughter] What you are aiming at

is to get perhaps the same level of intelligence in the translated

rhyme that

is there in the original. If I pride myself on anything, I pride myself

on the

quality of my rhymes, above all. If I have any ambition, indeed it's to

be

considered a good rhymer. [laughter] ss: That's

not a meagre ambition for a traditional poet, for a classical poet,

given your

roots, your background. JB: The main

question with free verse-it's not my expression, it's Eliot's-the main

question

with free verse is,

Free from what? The whole point is that, well, free verse has emerged

presumably as a monument of a personal departure, of a personal crisis,

of this

or that great individual. In English it would be Eliot. The crucial

word, the

crucial aspect, is development. And you can't have development without

some

great change. And people who undertake to write poetry in free verse

simply

have to, in a sense, repeat the same development. Otherwise they just

buy the

net result, they repeat what they have read, what they have inherited.

Remember

Goethe's warning that you must earn what you inherit. It's really

daunting

because you have no sense of freedom unless you've worked for it. ss: Would

you qualify that remark, or that kind of criticism, with reference to

someone

like Czeslaw Milosz, who begins as a very formal poet and then moves

back and

forth between free and more traditional verse? JB: Indeed,

what happened to him is exactly the same thing that occurred in the

case of,

well, Eliot and Pound. They started as highly formal poets. If it's a

cultural

development, if it's a natural development, if it's organic, well then

we have

to get to the entire organism of a culture, the entire nature of its

poetry. I

do on occasion write something in free verse, indeed in Russian or in

English.

But you don't get the sense of cadence in the language you write

unless, well,

unless you already have it in your bloodstream, the beats, the rhythm

because

it's your first language. Well, that's my belief. I don't believe I'm

mistaken. [laughter] ss: Let me

pursue this question of translation. In one of your essays, you

describe

bringing Mandelstam's poems in translation to Auden, and Auden not

being

convinced of Mandelstam's greatness. I think we have all had a

disappointing

experience reading Goethe, Pushkin, or Heine in translation. Of the

four major

Russian poets whose tradition you're carrying on-Mandelstam, Pasternak,

Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova-which one do you think is the easiest to translate

and

most rewarding when read in translation? JB: Oh, Miss

Akhmatova. Theoretically and pracctically, in many ways, Akhmatova. The

thing

with Akhmatova, the reason I'm saying Akhmatova, well, she's sort of,

if you

will, a minimalist. She resorts to very simple means. And I would

think a translation of her poetry can be done in English effectively. I

can

think of an American poet similar to her, Louise Bogan. In both of

them, the

poet starts and from the first line you are right there, you're in

business.

There is no warming up. And Akhmatova never wrote anything on an epic

scale.

Her longest work was something like four hundred lines. ss: Do you

like the Max Hayward/Stanley Kunitz versions of the poems? JB: No.

Well, I'm afraid that I made enemies with Mr. Kunitz over that. [laughter] ss: I'll

take that question back. JB: No, no.

There are also the translations by what's his name? Walter Arndt. It's

a good

edition, except that ... well, he embarked on a big project, he tried

to do

quite a lot. Something like over a hundred poems. And presumably he was

doing

that in one sitting. Not in one sitting perhaps. Well, in a year or

two. So in

that they became a little soupy, they're watered down a bit. There is

also the

two-volume edition of the collected poems by Judith Hemschemeyer, a

Slavicist,

and Roberta Reeder, Akhmatova's biographer. But that's done in what

amounts to

free verse, and we would think that once we've got the free verse, once

we

don't have the constraints of rhyme, well, it's not quite Akhmatova.

Besides,

the idea of translating a poet into a different language, well, perhaps

it

bespeaks chutzpah rather than intelligence. ss: Yet you

have been translating since the 1960s when you did versions of Polish,

Spanish,

and Serbo-Croation poems as well as poems by Eliot, Auden, and Donne.

Have you

ever been tempted, given your present command of English, to translate

Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, or Pasternak? JB: I've

done a little here and there, but not much. I translated

a few poems of Mandelstam, I translated a few poems of Tsvetaeva, I

translated

a couple of Pasternak's, a couple of Nabokov's. I didn't try Akhmatova,

because, well ... I don't really know why. Maybe it's because there are

so many

other translations today, almost a translation industry. It's rather

interesting it's happening this way because I think you would agree

with me

that me that if you look back, practically in every decade, starting

somewhere in

the I960s, a great Russian poet from the past has emerged in English.

Pasternak, then

Akhmatova, and then Mandelstam. And finally now Marina Tsvetaeva. It's

very

interesting how we can always identify a decade by a particular poet.

But

there's something more to say about this, and the emergence of those

great

four. Of course, there weren't only four. There were several other

poets who

were completely overlooked. Within two or three more decades, we'll see

a

revival- or an arrival, rather-of people like Vladislav Khodasevich.

But what's

interesting about the four is I think they will always remain the four.

ss:

Akhmatova has a poem called "We Four." It's quite short, and it might

be worth reading even if it is the Hayward/Kunitz version. Herewith I

solemnly renounce my hoard Did I say

two? ... There by the eastern wall, November

1961 (in delirium) JB: Yes,

that's right. The poem suggests a very peculiar aspect that you might

think

doesn't directly belong to the reading or history of poetry, but it's a

very

humane aspect. Four poets who at some deep level belong together. If

you think

about ancient Rome, well you can think also about four important poets.

You can

think about Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Propertius, though he's a little

chronologically

off. But even if Propertius is a bit later than the others, he's still

related

to them and the time. What we're talking about here is four very

well-known

poets and an era. And both in Rome and Russia they arrived, those

poets, at a

time of great crisis in their societies, on the eve of the great war

and

revolution in Russia and at the time of civil war and Augustus in Rome.

And

that's why they will remain important in this way, no matter the

presence of

other people with great talent, and there were many. The four will

remain. is: You've

written relatively critically of Russian prose during the Soviet era.

You

singled out Andrei Platonov as an exception. I think you also mentioned

Boris

Pilnyak? JB: No, no.

Not Pilnyak. ss: Okay, so

we'll stick with Platonov. With his exception, you were fairly gloomy

about the

history and prospects of Russian prose during the Soviet era. Your

essays

reminded me, in fact, of Gunter Grass writing after the Second World

War, I

think in the 1950S and 1960s, about the damage that had been done to

German

prose and German poetry by the enforced propagandistic, didactic

attitude to

language during the Nazi era. Do you have a sense that Russian

literature can

recover from nearly a century of abuse? JB: You

know, I think it will take less time for Russian to recover its health.

Russia

is a very populous country, and the language is such that given the

size of,

the volume of, the nation and the number of practitioners involved,

it's bound to

generate something rather quickly out of its JB historical situation.

The thing

is that even now there's a wonderful process going on. I don't really

keep both

my eyes on what's going on. It's one eye, perhaps. [laughter] Even the one eye

blinks now and then because there's a great deal of literary and

cultural

activity. The poetry's rather wonderful. The vitality of it today is

just,

well, extraordinary. Nobody knows a thing about it here in the West.

Now it's

even getting more difficult because in the bad old days there was a

centralization

of the culture. So whoever was at the top or in a prominent position or

whatever was at least well known. So therefore a reputation could be

created

fast, or faster than now, because now it's all decentralized. It's, for

all

intents and purposes, like the situation in the West. We don't know our

poets to begin with. That's one point. Another point is we pay

attention to one

or two at the expense of all the others. What's in general quite

peculiar is

the tendency of any culture to appoint at a certain period, a certain

decade, a

certain era, a certain generation, but very often even for a century,

one great

poet. It has to do obviously with laziness on the part of the reading

public,

also on the part of those who are in charge of publicity and education.

Providence takes care or tries to take care of humanity, of the nation,

of the

speakers of that language; it provides the public, the nation, with

poets.

Well, they elect one or two and push all the rest to the side. ss: Since

you've mentioned great poets, I wonder if we could turn the

conversation to one

of the century's greatest, Wystan Hugh Auden. JB: Gladly.

[laughter] ss: You

mention in your essay "To Please a Shadow" that one of the reasons

that you learned English, or became more and more deeply involved with

it, was

"to find myself in closer proximity to the man who I consider the

greatest

mind of the twentieth century, Wystan Hugh Auden." And then you discuss

his various qualities. The ones I particularly like are his

"equipoise" and "wisdom." What has Auden's role been in

your career as a poet? JE: I'll

answer this question if I can. He entered me, in a sense, he entered my

life. We

are speaking, well, I am sitting here and I feel that I am part him.

You may

take me to the loony bin right away. [laughter] I spoke earlier today

about

him, and basically one doesn't want to repeat oneself within the course

of a

day, but perhaps I should. When I met him twenty-two years ago in 1972,

I was

thirty-two years old and he had only one year left to live. I knew

fairly

little about him. I knew about some of his poems. I had translated some

in

Russia. It had all started rather in a peculiar way, in a funny way. In

1965, I

showed my poems to a great friend of mine, and he read them and he

said, Well,

it's so much like Auden, it sounds much like Auden. And to my

ears-remember,

it's the 1960s-it was a great compliment in many ways because in the

1960s, all

we knew about poetry in English was T. S. Eliot and then Auden. If you

can

imagine my English, this English, let's say thirty-five years ago, I

tried to

make my way through his poems. When I met him I knew some twenty or

thirty

poems of his. The one long poem I had read by that time was "Letter to

Lord Byron," which is a great work. At any rate, then he dies, and then

I

begin to read him more seriously, and this grows year after year after

year.

He's been growing in me ever since. It's a very peculiar process. Well,

I said

he has entered me. Indeed. I think I can take practically anything

because he

took so much. I am prepared to die because he died. I would like to be

as

intelligent as he was. And it's a wonderful intelligence, it's a

flattering

intelligence. When you read him, he flatters you. He makes you

intelligent.

It's impossible to say the same about anyone else I know. I don't

really know

what to say, but I could say a lot more. [laughter] ss: In the

same essay you talk about how it's imporrtant for every reader to have

at least

one poet that they love cover to cover. Auden is obviously one of the

poets you

are devoted to. Who are some of the other poets you think highly of?

For

instance, would you approve of someone devoting themselves to the

poetry of

Eugenio Montale to the extent that you have devoted yourself to

Auden's? JB: Oh yes,

Montale is worth it, definitely. I think since this is a predominantly

English-speaking country I will speak of English poets. I would say

that Thomas

Hardy is definitely worth it. You should read him, a wonderful poet.

He's one

of the greatest figures, though a far greater poet than a prose writer.

I would

also include Robert Frost, no question about it. I think perhaps I'm

even

closer to Frost than to Auden. It's a more tempting posture. Do you

remember

when Lionel Trilling called him a terrifying or terrible poet? I

wouldn't

recommend Wallace Stevens. He's no doubt an important figure, but for

me, he's

far too much of a fantasizing aesthete. I mean this as a compliment,

not a

put-down, but it would take too long to explain what I mean. [laughter] I would

say Eliot, of course. I would also say Elizabeth Bishop. She is

Canadian by

birth. So there are plenty. And obviously, as I speak, you probably

know, when

you talk in this manner you overlook somebody and then it comes back to

you.

Among the foreigners, those who I wanted to read in translation, well,

you've

got Milosz already. I would add two more Polish poets. One is Zbigniew

Herbert,

and another is Wislawa Szymborska, a wonderful lady. ss: Both

write in free verse. JB: Both of

them do. But they've earned the right to do so, and I'll tell you why.

It's not

exactly my argument; it's Milosz's own argument. In his Norton

Lectures, I

think, he puts forth the following idea to explain why Polish poetry is

abandoning

traditional metres. It's because, he says, in Poland the traditional

verse has

been identified with the culture and world order that brought the

country to

catastrophe. So, in a sense, traditional verse is the verse of the old

guys,

the past. ss: I asked

Czeslaw Milosz about a week after he won the Nobel Prize whether he

ever

worried about losing his command of Polish because of his long exile.

Has this

ever troubled you? JB: Yes, I

worried about that. Especially initially, I did. Now I don't, perhaps

to my own

detriment, but I don't. I'm simply of the mind that we're all being

brought up

to believe that it's the diction of the street, of the people, that

literature

should abide by. I'm of the opinion that it's the other way around.

It's the

street that should abide by the language of literature. Dante is an

illustrious

example. I think Italians today speak, or at least are capable of

speaking, not

the discourse of the street or television but of their literature. When

I feel

anxious about all this I think about somebody like the great Greek poet

Constantine Cavafy, who wrote in a language that wasn't Greek. It

wasn't

demotic or what the Greeks calls katharevousa. At best it was the idiom

of the

Greek colony in Alexandria, in Egypt. And yet it resulted in great

poetry. ss: As you

know, Cavafy was also a favorite of Auden's, who wrote a fine

appreciation of

his poetry. Now that we have circled back to the beginning, perhaps

this is a

good place to stop. Thank you for sharing your thoughts on poetry with

us this

afternoon. |