|

|

Album

|

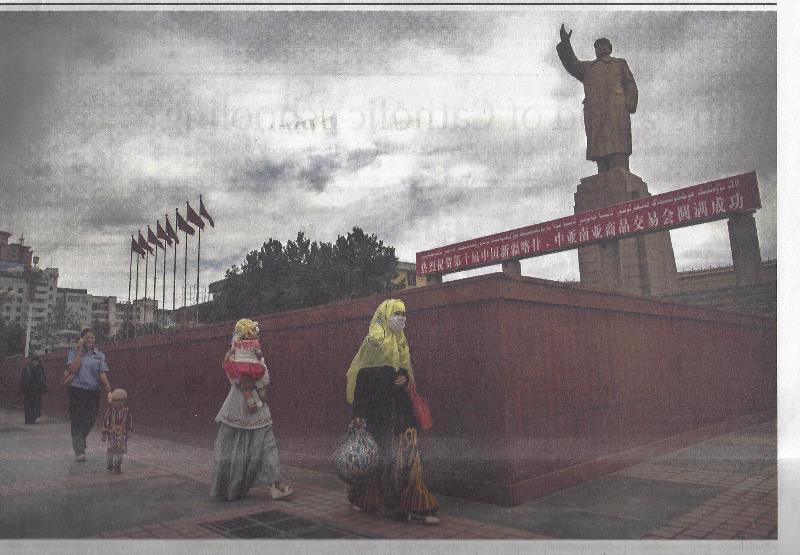

Hình chụp

trong cuộc biểu diễn lực lượng của Hồi Giáo ở Luân Đôn,

Pictures

from London:

These

pictures are of Muslims marching through the STREETS OF LONDON during

their

recent 'Religion of Peace' Demonstration.

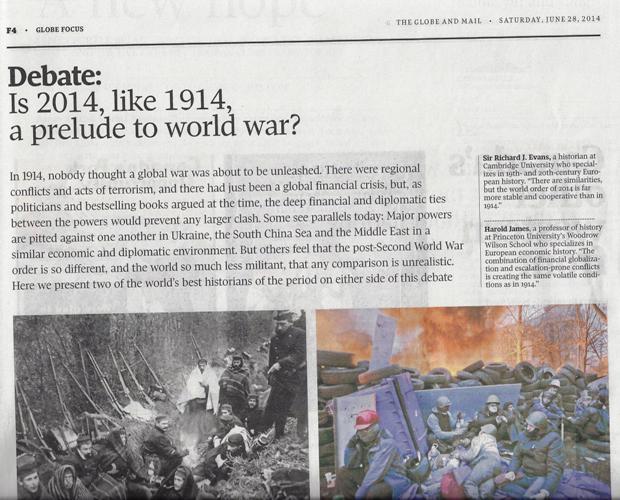

Tờ Globe and

Mail, Toronto, đã coi năm 1914 mở ra cuộc Thế Chiến, có gì tương tự với

2014

Is 2014,

like 1014, a prelude to world war?

Liệu 2014, như 1914, con

chim "báo bão"?

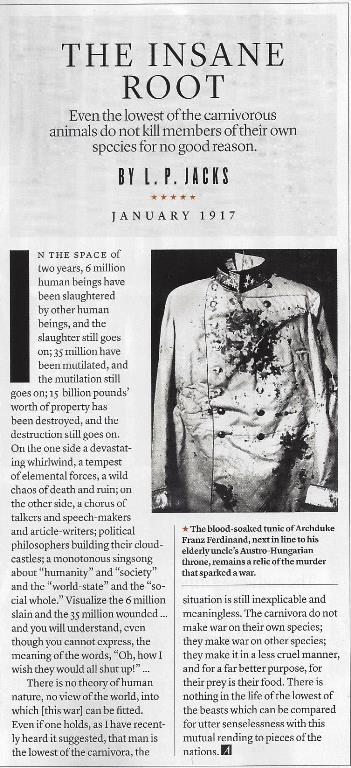

Thằng bé,

the boy, làm thịt Archduke và mở cánh cửa cuộc chiến toàn cầu [The

Globe and

Mail]

Mít, khùng,

như GCC, làm sao mà không nghĩ đến cú Văn Cao làm thịt tên “Việt Gian”

DDP, mở

ra cuộc chiến Mít lần thứ nhất?

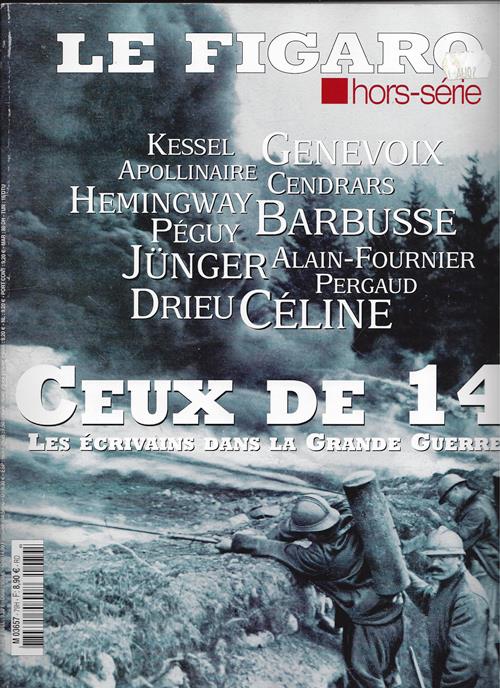

1914-2014

Mặt Trận Miền

Tây Vưỡn Yên Tĩnh, cuốn tiểu thuyết best-seller nhất của thế kỷ!

Thua "Lỗi Buồn Chiến

Tranh" của Bảo Ninh:

Không giống như Mặt Trận Miền Tây Vẫn

Yên Tĩnh, đây là một cuốn tiểu thuyết không chỉ về chiến tranh. Một

cuốn sách về chuyện viết, về tuổi trẻ mất mát, nó còn là một câu chuyện

tình đẹp, nghẹn ngào [Lời giới thiệu của Geoff Dyer trên tờ Independence, in

lại trong bản dịch tiếng Anh của Nỗi Buồn].

Tình cờ, vớ

được số báo cũ, trong cái mớ hầm bà làng-thùng rác cuối đời, 1 bài

viết, cũng của

Simic, về, cũng cuộc chiến đó, mà ông là 1 đứa con nít, “tù nhân nằm

trong nôi”-

chữ của Thảo Trường, khi chứng kiến vụ Trần Trường –

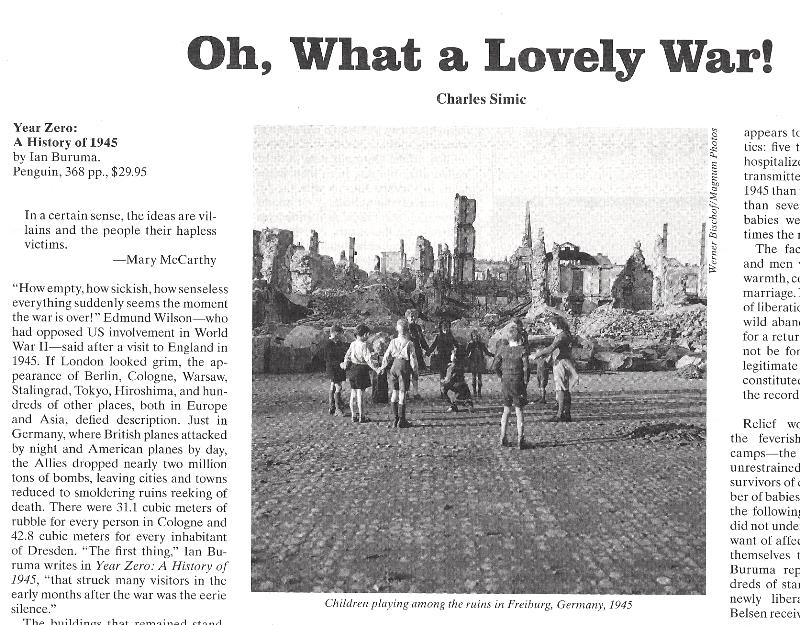

Cái tít, “Ui cuộc

chiến mới

đẹp làm sao”, thì có thua gì câu thơ, "Đường ra trận mùa này đẹp lắm"?

Bài này cũng thật là tuyệt cú mèo, hà, hà!

NYRB Oct 10, 2013

Oh! What a Lovely War!

1914-2014

Is 2014,

like 1014, a prelude to world war?

Liệu 2014, như 1914, con

chim "báo bão"?

Thằng bé,

the boy, làm thịt Archduke và mở cánh cửa cuộc chiến toàn cầu [The

Globe and

Mail]

Mít, khùng,

như GCC, làm sao mà không nghĩ đến cú Văn Cao làm thịt tên “Việt Gian”

DDP, mở

ra cuộc chiến Mít lần thứ nhất?

Đúng là như

thế.

Bởi là vì cuộc

chiến Mít thứ nhất nổ ra, do dã tâm của VC, phải làm cỏ sạch các đảng

phái

khác, khi choàng cho chúng cái nón Việt Gian, theo Tây. Muốn như thế,

thì phải

nổ ra cuộc chiến.

Những tài liệu

Gấu mới được đọc, của tụi Tẩy, xác nhận điều này. Cuộc chiến chống Pháp

có thể

không xẩy ra, nếu Việt Minh thực tình không muốn gây chiến.

Cũng thế là

cuộc kháng chiến thần thánh chống Mẽo cứu nước: Phải làm cho cuộc chiến

nổ ra,

để đẩy cả một miền đất vào thế… Ngụy, trừ

đám nằm vùng. Cú đầu độc tù Phú Lợi, do VC phịa ra, để có cớ thành lập

MTGP, Mẽo

hoảng quá, bèn đổ quân vô!

Giả như không

có cú Phú Lợi, thì cũng phải phịa ra nó. Mẽo cũng dùng đòn này, để rút

ra khỏi

cuộc chiến Mít, khi ngụy tạo cú Vịnh Bắc Bộ.

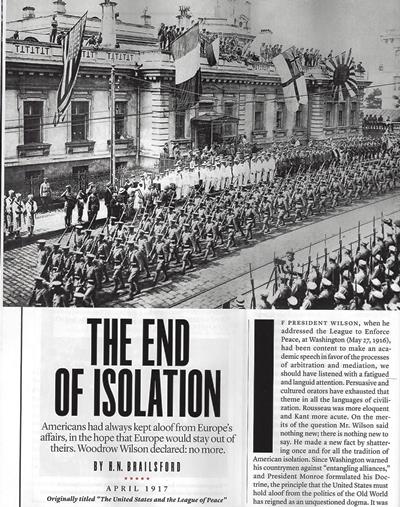

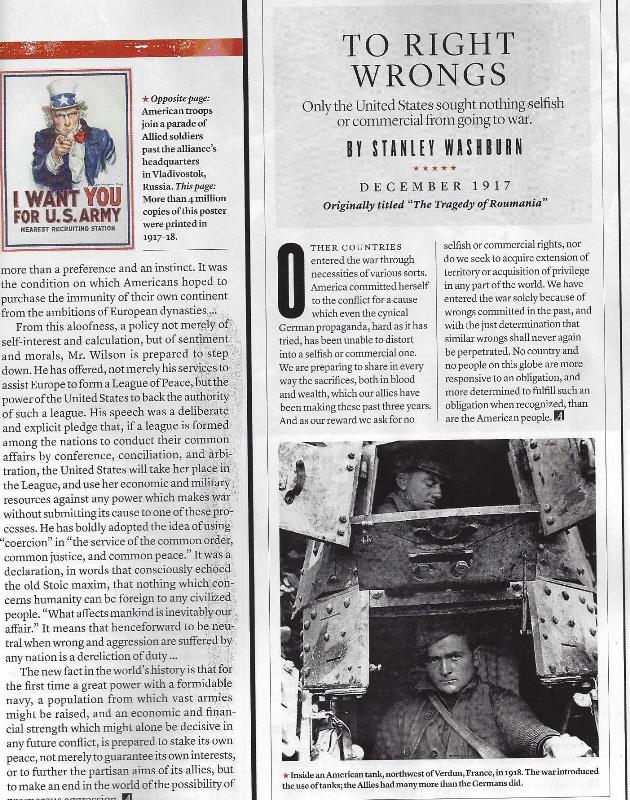

Trong

Thế Chiến 1914, Mẽo là nước độc nhất tham

gia, không vì vị kỷ, và đó là do tổng thống Mẽo, Woodrow Wilson, muốn

như thế!

No

More Isolation!

[Báo Atlantic, số đặc biệt về

WWI, July, 2014]

1914-2014

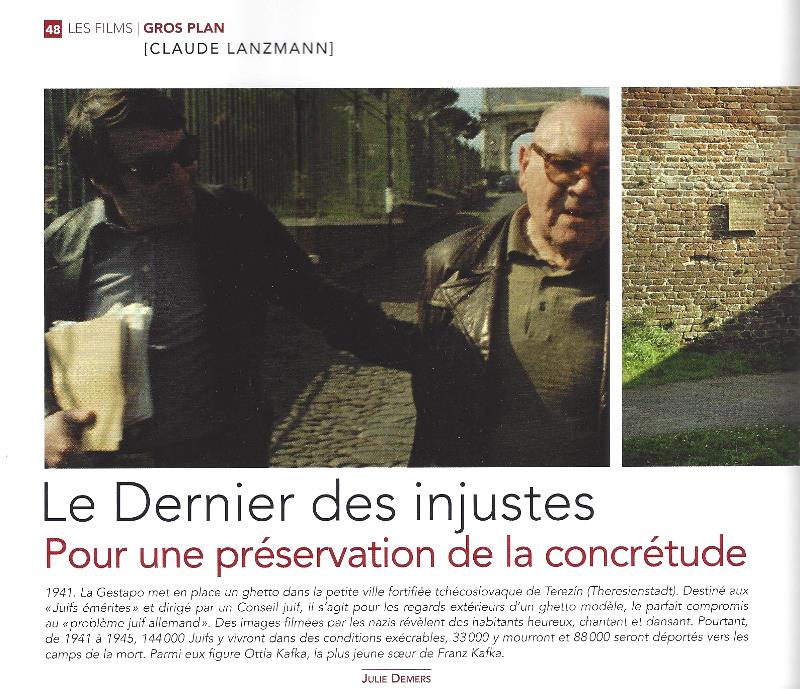

Kẻ bất trung thực cuối cùng

The

Defense of a Jewish Collaborator

Tại sao mi sống

sót?

[Pourquoi avez-vous survécu?]

Còn mi thì

sao?

[Et vous?]

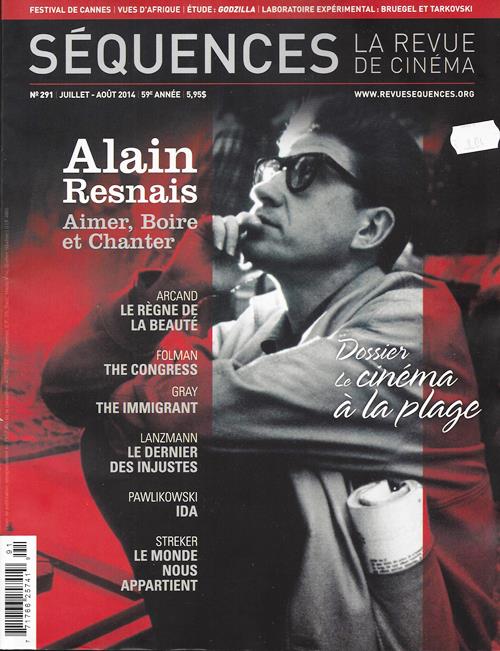

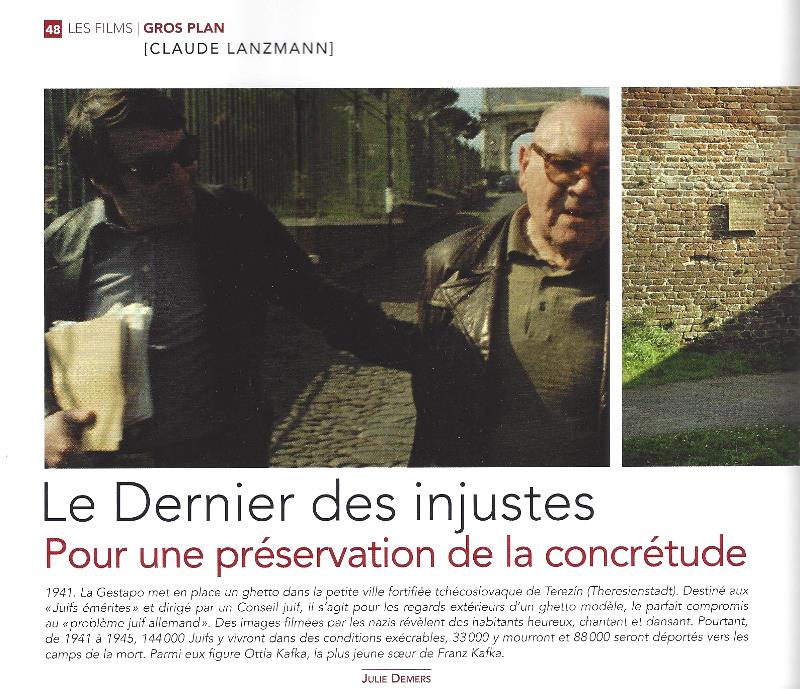

“Kẻ bất

trung thực cuối cùng”, là 1 phim đối trọng, contre-poids, với phim Lò Thiêu, Shoah, cũng của Lanzmann. Tên

phim cũng là nick của nhân vật chính trong phim, 1 tên Do Thái đã từng

cộng tác

với Nazi, một trong những Trưởng Trại của một ghetto kiểu mẫu, được

thiết lập để

trình ra cho nhân loại thấy, ở tù Nazi sung sướng như thế nào.

The specter

of Hannah Arendt haunts every film Claude Lanzmann has made, beginning

with his

nine-and-a-half-hour epic Shoah, released in 1985. Arendt believed that

the

Nazi experience could be understood, and had to be, since only through

understanding can “we come to terms with, reconcile ourselves to

reality, that

is, try to be at home in the world.” This would mean reconciling

ourselves, in

some sense, even to the Holocaust. “To the extent that the rise of

totalitarian

governments is the central event in our world,” she once wrote, “to

understand

totalitarianism is not to condone anything, but to reconcile ourselves

to a

world in which these things are possible at all.”

Lanzmann

refuses to understand the Holocaust, let alone make peace with the

world that

made it possible. A short essay only three paragraphs long is his most

powerful

retort to Arendt:

All one has

to do, perhaps, is pose the question simply, and ask, “Why were the

Jews

killed?” This shows its obscenity. There is an absolute obscenity in

the

project of understanding. Not understanding was my iron law during all

the

years of preparing and directing Shoah: I held onto this refusal as the

only

ethical and workable attitude possible…. “Hier ist kein Warum”: this,

Primo

Levi tells us, was the law at Auschwitz that an SS guard taught him on

arriving

at the camp: “Here there is no why.”

Bóng

ma Hannah Arendt ám ảnh mọi phim của Claude Lanzmann, bắt đầu với sử

thi Lò Thiêu dài 9 tiếng

rưỡi, ra lò năm 1985. Arendt tin rằng

kinh nghiệm Nazi có thể hiểu được,

và sự tình phải như thế, bởi là vì, chỉ thông qua hiểu biết chúng ta

mới có thể

xoay sở được với thực tại , nghĩa là, cố “ở nhà” với thế gian, coi nó

là nhà của

mình.

Theo nghĩa đó hãy cố mà sống, ngay

cả với Lò Thiêu…

Lanzmann

đếch chịu thế, hà, hà!

Amos Oz cho

biết, khi coi phim Shoah, une

histoire orale de l’Holocauste, của đạo diễn Claude Lanzmann, một

trong những xen rất ư là bình thường, chẳng có tính điện ảnh, nhưng bám

chặt vào ký ức ông. Đó là xen, kéo dài chừng 15 phút, chiếu cảnh

Hilberg - ngồi trong căn phòng xinh xắn, tại nhà của ông, ở Vermont,

[người ta nhìn thấy, qua cửa sổ, bên ngoài cây cối, tuyết, bên trong,

những cuốn sách, ngọn đèn bàn] - giải thích cho nhà đạo diễn Claude

Lanzmann, nội dung một tài liệu đánh máy, tiếng Đức, chừng 15 dòng, gồm

những dẫy số.

Một “ordre de route”, (lệnh chuyển vận) của chuyến xe lửa số 587, do

Gestapo Berlin,

chuyển cho Sở Hoả Xa Reich, “lưu hành nội bộ”.

Một bí mật nằm ở nấc thang chót, của bộ máy giết người.

Hilberg giải thích: “Chìa khóa tâm lý của toàn thể chiến dịch, là:

không bao giờ được sử dụng những từ có ý nghĩa hoàn toàn rõ rệt. Tối

giản tối đa, chừng nào còn có thể tối giản, ý nghĩa của chiến dịch sát

nhân, đưa người tới Lò Thiêu. Ngay cả dưới mắt của chính những tên sát

nhân.”

Thú thực, trước đây, nói gì thì nói, Gấu vẫn không hiểu tới tận nguồn

cơn, tại làm sao mà lại gọi "đi tù" là "đi học tập cải tạo", tại sao

lại dùng một mỹ từ như thế, cho một từ bình thường như thế, như thế,

như thế... cho đến khi đọc Oz. (1)

Nó làm Gấu

nhớ đến cái chết dởm của mấy tên tù VC, ở trại tù Phú Lợi, mở ra cuộc

chiến Mít

lần thứ nhì, làm chết trên 3 triệu Mít, và làm tiêu luôn nước Mít.

Tuy nhiên,

nó còn làm Gấu nhớ đến bài thơ của Auden, được nhà

thơ Mẽo

Robert Hass vinh danh sau đây:

Bài thơ chấm

dứt một ngàn năm

Chính là vì,

phải tìm đủ cách ăn cướp Đàng Trong, mà lũ Bắc Kít đã rước họa Tầu Phù

vô “Đàng

Ngoài “ Chúng quên nỗi nhục nô lệ thằng Tầu 1 ngàn năm.

Bi giờ nghe

tụi chúng chống Tẫu, lèm bèm về “thoát Trung”, Gấu thấy tởm, cực tởm!

Tuy nhiên bài thơ

thần sầu này chẳng

mắc mớ gì tới ba cái chuyện nhơ bửn đó.

Nó làm nhớ đến ông anh nhà thơ, qua những

câu như:

A few

thousand will think of this day

Mad Ireland hurt you into

poetry

For poetry makes nothing

happen: it survives....

WWI

CENTENARY

On July 28th

it will be 100 years since the first world war broke out. Its

battlefields have

long since turned into centres of remembrance, destinations for school

trips.

In this photo essay, Brian Harris captures their stillness and symbolism

From

INTELLIGENT LIFE magazine, July/August 2014

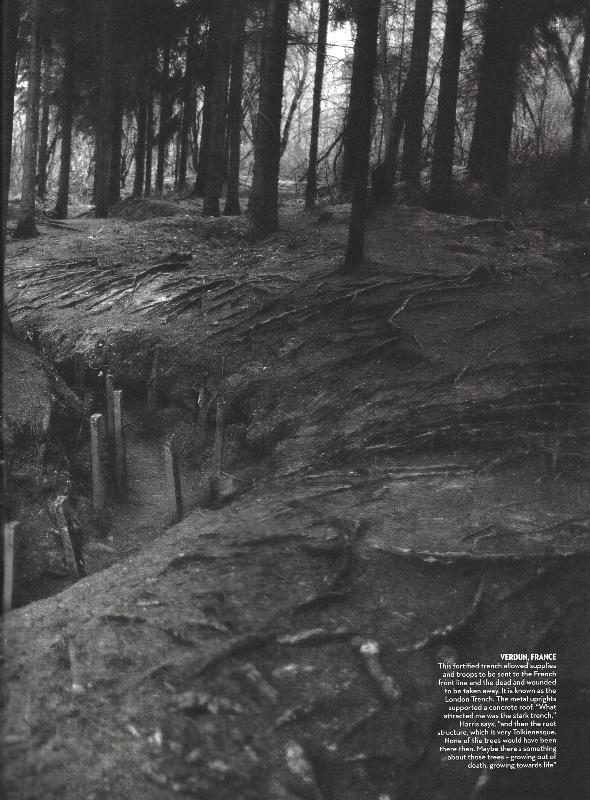

One evening

last March, Brian Harris stopped his car at the side of the road near

Douaumont

in north-eastern France and walked into the forest. After about 50

yards he

came to a trench winding its way through the trees (see photo four).

He’d been

there earlier in the day, but the light had been too sharp, the shadows

cast by

the trees too deep, and children from a school party had been running

up and

down the trench, their picnic laid out nearby. But now the light was

softer,

and the woods were gloomy and quiet. “I wanted to photograph the

darkness where

that trench went,” he says. “I knew that if you dug down into that

ground you

would find bits of body. In that forest there are the remains of men.

Those

roots are feeding off men.”

He was

standing on the Verdun battlefield, one of the bloodiest of the first

world

war, which began 100 years ago this July. During ten months of fighting

in

1916, up to 976,000 French and German soldiers were killed or wounded

at

Verdun. Many of the dead were never found. “To stand in a wood and

listen to

the quiet,” Harris says, “and realise that 100 years ago, where you’re

standing, was carnage—that’s chilling.” The trench he photographed led

from

Belleville to the front line and the fort at Douaumont. “It was a

pathway to

death.” His image—haunted, sombre, terrifyingly tranquil—is his elegy.

AISNE-MARNE

AMERICAN CEMETERY, BELLEAU, FRANCE

There are

2,289 graves here, at the foot of the hill where the battle of Belleau

Wood was

fought in June 1918. When Brian Harris was there, a new watering system

was

being installed, so the grass wouldn’t be parched for the centenary. He

was

struck by the effect. “It’s emotive. If you want the water to be rain,

it’s

rain. If you want it to be tears, it’s tears”

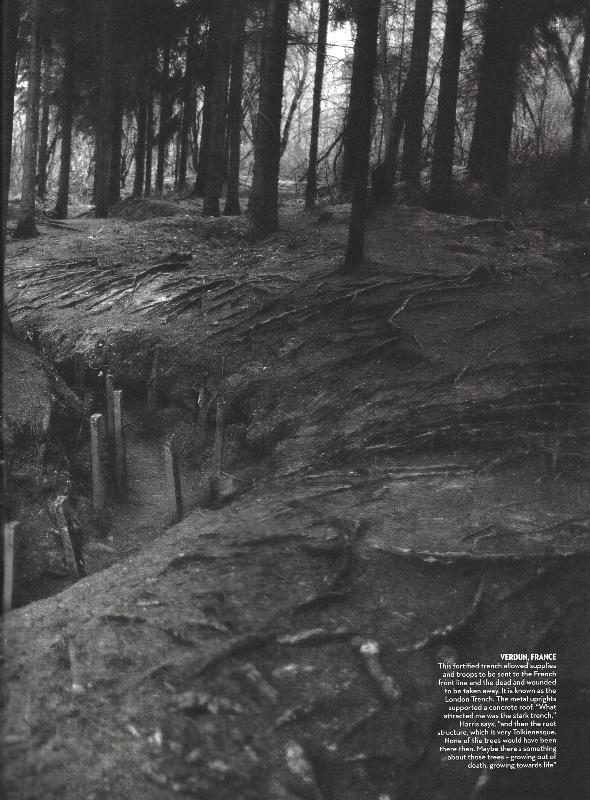

VERDUN,

FRANCE

This

fortified trench allowed supplies and troops to be sent to the French

front

line and the dead and wounded to be taken away. It is known as the

London

Trench. The metal uprights supported a concrete roof. “What attracted

me was

the stark trench,” Harris says, “and then the root structure, which is

very

Tolkienesque. None of the trees would have been there then. Maybe

there’s

something about those trees—growing out of death, growing towards life”

Liên tưởng

khùng làm GCC nhớ tới “Đường Mòn HCM”. Chỉ có khác, là, 1 con đường và

những

cây của nó, ở đây, đem đến đời sống.

Đường Mòn HCM, đem đến cái chết cho cả 1 xứ

Mít!

Intel

Life

1914-2014

VERDUN,

FRANCE

This

fortified trench allowed supplies and troops to be sent to the French

front

line and the dead and wounded to be taken away. It is known as the

London

Trench. The metal uprights supported a concrete roof. “What attracted

me was

the stark trench,” Harris says, “and then the root structure, which is

very

Tolkienesque. None of the trees would have been there then. Maybe

there’s

something about those trees—growing out of death, growing towards life”

1914-2014

Nó làm Gấu

nhớ đến cái chết dởm của mấy tên tù VC, ở trại tù Phú Lợi, mở ra cuộc

chiến Mít

lần thứ nhì, làm chết trên 3 triệu Mít, và làm tiêu luôn nước Mít.

Tuy nhiên,

nó còn làm Gấu nhớ đến bài thơ của Auden, được nhà

thơ Mẽo,

Robert Hass vinh danh sau đây:

Bài thơ chấm

dứt một ngàn năm

Chính là vì,

phải tìm đủ cách ăn cướp Đàng Trong, mà lũ Bắc Kít đã rước họa Tầu Phù

vô “Đàng

Ngoài “ Chúng quên nỗi nhục nô lệ thằng Tầu 1 ngàn năm.

Bi giờ nghe

tụi chúng chống Tẫu, lèm bèm về “thoát Trung”, Gấu thấy tởm, cực tởm!

Tuy nhiên bài thơ

thần sầu này chẳng

mắc mớ gì tới ba cái chuyện nhơ bửn đó.

Nó làm nhớ đến ông anh nhà thơ, qua những

câu như:

A few

thousand will think of this day

Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry

For poetry makes

nothing happen: it survives....

Although most of the pictures here were taken last

winter, they are the result of a 45-year fascination. In 1969, when he

was 16 and living in Romford in Essex, Harris went on a school trip to

Belgium. “We stayed in Blankenberge, played on the beach, got drunk on

Stella Artois. And we went to Tyne Cot cemetery on the battlefields of

Passchendaele. None of us had a clue. I was utterly taken by what I

saw. I just couldn’t believe that each headstone represented a life.”

Two weeks later, he joined a Fleet Street picture agency

as a messenger boy. He went on to become a photographer at the Times

and then the chief photographer at the Independent in its

early days, when it was bringing a new elegance and soulfulness to

newspaper pictures. As well as covering famines, presidential campaigns

and the fall of the Berlin Wall—a subject he returned to

for Intelligent Life in 2009—Harris’s interest

in the war kept taking him back to those battlefields and cemeteries.

“I did little stories about the re-carving of headstones, or the burial

of bodies.” In 2007 he collaborated with the writer Julie Summers on a

book called “Remembered”, a photographic history of the Commonwealth

War Graves Commission. “I see myself as a historian with a camera,” he

says.

LA BOISELLE, FRANCE

The wreath that brought the crown of thorns to mind. It

overlooks the Lochnagar crater, left by a mine detonated

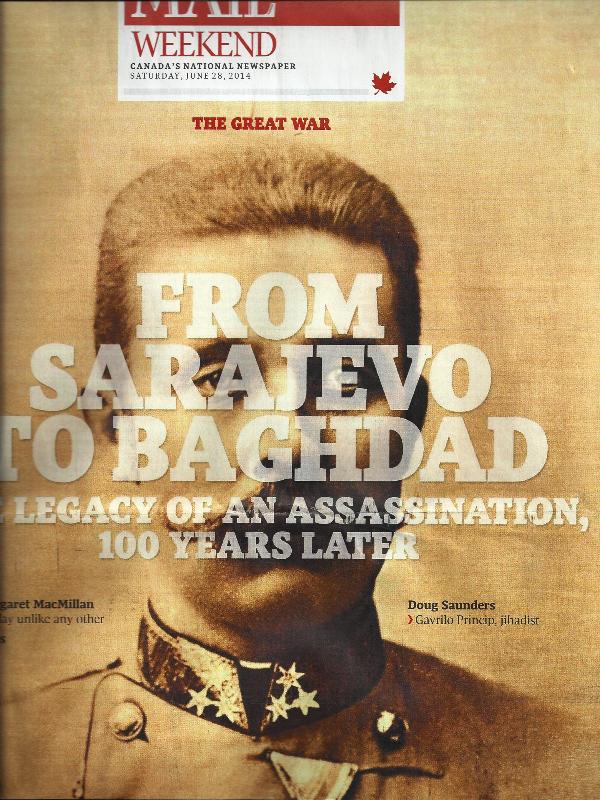

Is 2014,

like 1014, a prelude to world war?

Liệu 2014, như 1914, con chim "báo bão"?

Thằng bé, the boy, làm

thịt Archduke và mở cánh cửa cuộc chiến toàn cầu

[The

Globe and Mail]

Re:

Sarajevo. Archduke Franz là thừa kế của vương quyền đế quốc Áo- Hung.

Cặp vợ chồng

viếng thăm Sarajevo, ngày 28 Tháng Sáu, 1914, chừng 1 giờ sau, thì cả

hai bị thằng

bé sinh viên Princip làm thịt

Note: Đây là

đề tài lèm bèm [debate] của tờ nhựt báo Globe and Mail, Toronto, số cuối

tuần, Sat, June, 2014.

Nó làm Gấu

nhớ đến cái chết dởm của mấy tên tù VC, ở trại tù Phú Lợi, mở ra cuộc

chiến Mít

lần thứ nhì, làm chết trên 3 triệu Mít, và làm tiêu luôn nước Mít.

Tuy nhiên,

nó còn làm Gấu nhớ đến bài thơ thần sầu của Auden, được nhà

thơ Mẽo

Robert Hass vinh danh sau đây:

Bài thơ chấm

dứt một ngàn năm [nô lệ thằng Tầu].

Chính là vì,

phải tìm đủ cách ăn cướp Đàng Trong, mà lũ Bắc Kít đã rước họa Tầu Phù

vô “Đàng

Ngoài “ Chúng quên nỗi nhục nô lệ thằng Tầu 1 ngàn năm.

Bi giờ nghe

tụi chúng chống Tẫu, lèm bèm về “thoát Trung”, Gấu thấy tởm, cực tởm!

Tuy nhiên

bài thơ thần sầu này chẳng mắc mớ gì tới ba cái chuyện nhơ bửn đó.

Nó làm GCC nhớ

đến ông nhà thơ, qua những câu, thí dụ như:

A few

thousand will think of this day

Một vài ngàn

năm sau sẽ nghĩ đến ngày này

Mad Ireland

hurt you into poetry

Ái Nhĩ Lan khùng

dùng dao đẩy ông vô thơ

[Việt Nam đói

nghèo quên ca dao]

For poetry

makes nothing happen: it survives.

Thơ làm chẳng

cái gì xẩy ra: nó sống sót…

DECEMBER 27 [1998]

A Poem for the End of a

Thousand

Years:

W.H. Auden

We are about

to enter the last year of the century and-I was going to write-of a

millennium,

but who, in fact, has any sense of the year 999, or for that matter

1132 or

1412? This last century has been more than enough for us to try to take

in. So

I found myself thinking about an appropriate valediction to this last

extraordinarily violent hundred years. Sixty years ago this January, on

the eve

of the Second World War, the Irish poet William Butler Yeats died. A

younger

English poet, W H. Auden, wrote an elegy for him. It's become a very

famous

poem. A winter like this one. The tenth year of an economic depression.

Hitler's military, having annexed Austria and the Sudetenland, is

drawing up

plans for the conquest of Europe. And an Irish poet dies:

In Memory of W B. Yeats

(d. Jan 1939)

I.

He

disappeared in the dead of winter:

The brooks

were frozen, the airports almost deserted,

And snow

disfigured the public statues;

The mercury

sank in the mouth of the dying day.

What

instruments we have agree

The day of

his death was a dark cold day.

Far from his

illness

The wolves

ran on through the evergreen forest,

The peasant

river was un-tempted by the fashionable quays;

By mourning

tongues

The death of

the poet was kept from his poems.

But for him

it was his last afternoon as himself,

An afternoon

of nurses and rumors;

The

provinces of his body revolted,

The squares

of his mind were empty,

Silence

invaded the suburbs,

The current

of his feeling failed; he became his admirers.

Now he is

scattered among a hundred cities

And wholly

given over to unfamiliar affections

To find his

happiness in another kind of wood

And be

punished under a foreign code of conscience.

The words of

a dead man

Are modified

in the guts of the living.

But in the

importance and noise of to-morrow

When the

brokers are roaring like beasts on the floor of the

Bourse,

And the poor

have the sufferings to which they are fairly

accustomed,

And each in

the cell of himself is almost convinced of his freedom,

A few

thousand will think of this day

As one

thinks of a day when one did something slightly unusual.

What

instruments we have agree

The day of

his death was a dark cold day.

II.

You were

silly like us; your gift survived it all:

The parish

of rich women, physical decay,

Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry,

Now Ireland

has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry

makes nothing happen: it survives

In the

valley or its making where executives

Would never

to tamper, flows on south

From ranches

of isolation and the busy briefs,

Raw towns

that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of

happening, a mouth.

III.

Earth,

receive an honored guest:

William

Yeats is laid to rest.

Let the

Irish vessel lie

Emptied of

its poetry.

In the

nightmare of the dark

All the dogs

of Europe bark,

And the

living nations wait,

Each

sequestered in its hate;

Intellectual

disgrace

Stares from

every human face,

And the seas

of pity lie

Locked and

frozen in each eye.

Follow,

poet, follow right

To the

bottom of the night,

With your un-constraining

voice

Still

persuade us to rejoice;

With the

farming of a verse

Make a

vineyard of the curse,

Sing of

human un-success

In a rapture

of distress;

In the

deserts of the heart

Let the

healing fountains start,

In the

prison of his days

Teach the

free man how to praise.

The

Bourse is the name of the French stock

exchange

Happy

New Year

Robert Hass: Now

& Then

|

|